The Paradox of Paper Money in a Digital Age

In an era where cash transactions are becoming increasingly rare for law-abiding citizens, a startling contradiction emerges. The value of dollar bills in circulation reached an unprecedented high of $2.345 trillion in April 2024, with similar peaks observed for the euro, British pound, Japanese yen, and Swiss franc. This surge occurs despite the fact that nearly half of the population now uses physical currency only a handful of times each year, with even street vendors equipped with card readers. The question arises: why are central banks worldwide producing more high-denomination banknotes than ever before?

The Dark Economy's Lifeline

The answer lies in the shadowy realms of international crime. While ordinary individuals face rigorous scrutiny when moving legitimate funds for purchases like appliances or vehicles, criminal enterprises operate with alarming ease. Drug traffickers and people-smugglers simply transport bundles of cash in suitcases or coat pockets across borders, sustaining their illicit operations. Despite growing efforts, such as increasing numbers of cash-sniffing dogs at airports, enforcement struggles to keep pace with the flood of banknotes issued by central institutions.

The term "money laundering" originated in 1920s Chicago, where figures like Al Capone used laundromats and small businesses to legitimise profits from bootlegging. Today, the methods have evolved in complexity. In modern Britain, the proliferation of barber shops in urban centres has sparked speculation about new laundering fronts, though conclusive evidence remains elusive. What is clear is that the infrastructure for cleaning dirty money continues to expand alongside criminal ingenuity.

Oliver Bullough's Investigative Mastery

Oliver Bullough stands as one of Britain's most formidable investigative journalists, combining thorough research with compelling narrative style. His work, including coverage of post-Soviet economies and the Chechen conflict, demonstrates remarkable courage—a vital trait when exposing international financial crimes. In his latest book, Everybody Loves Our Dollars, Bullough elevates investigative reporting beyond sensationalism, driven by a profound moral purpose that scrutinises the global economic underworld.

Bicester Village: A Laundering Hub

Bullough's investigation begins in an unlikely locale: Bicester Village, the Oxfordshire retail outlet designed as a quaint New England town. Here, luxury brands like Gucci, Louis Vuitton, and Stella McCartney offer discounted goods to an international clientele. Train announcements in Arabic and Mandarin signal the target market, with shoppers often departing with expensive suitcases packed for destinations like Bahrain or Chongqing.

Bullough argues this consumer frenzy constitutes a significant money-laundering channel. A senior police officer outlines a typical scheme: Chinese factories ship drugs to UK gangs, who pay Chinese students in cash. These students then purchase luxury items at Bicester Village, either directly or after depositing funds, and ship goods back to China, effectively moving illicit money across borders.

The Central Bank Profit Motive

The journey leads to the heart of the issue: central banks' lucrative incentives. At facilities like the US Federal Reserve's Western Currency Facility in Texas, vast quantities of $100 bills are printed daily. Astonishingly, approximately 70% of all $100 bills circulate outside the United States. Each note, costing pennies to produce, represents an interest-free loan to those who withdraw it, generating tens of billions in revenue for the Federal Reserve alone. This profit margin proves too enticing for central banks to abandon, regardless of consequences.

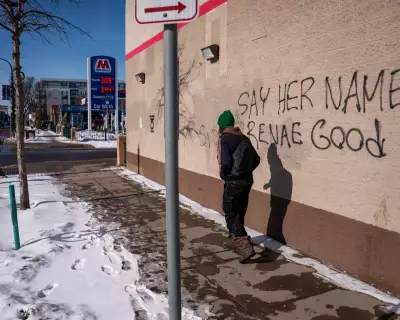

The Human Cost of Cash

The repercussions are devastating. In Mexico, which absorbs around $25 billion in US banknotes annually, drug violence claims about 150 lives daily. Since 2006, nearly half a million people have been murdered in cartel-related conflicts. Bullough highlights the story of an investigative journalist in Ciudad Juárez, beheaded for exposing cartel secrets—his young son discovering the grisly scene. His widow describes wiping blood from his face, a trauma that haunts her sleepless nights.

This represents just a fraction of the global toll exacted by central banks' profit-driven policies. As Bullough concludes, the war on drugs has long been lost, and the battle against money laundering is faltering—governments prioritise revenue over reform. The true price is paid by individuals like the journalist's widow, for whom designer handbags symbolise a cycle of violence funded by paper currency. John Simpson, the BBC's world affairs editor, underscores the urgency of Bullough's exposé, a stark reminder of cash's deadly legacy in an increasingly digital world.