Money transfers sent through mobile phone applications to family members in Africa are commonly known as the 'black tax'. This practice sees workers across the continent and in the diaspora using their salaries to provide a safety net for extended relatives, blending financial burden with a sense of pride.

The Financial and Emotional Weight of Remittances

From Senegal to Somalia and Egypt to South Africa, notifications from fintech apps like Western Union or WorldRemit often dictate the daily, weekly, or monthly mood for many. These transfers, referred to as the 'black tax', mean that one individual's earnings and success can support an entire family network.

For those dispatching funds, the payments represent both a heavy load and a badge of honour. In Lagos, Nigeria's economic hub, salaried employees reported last year that around 20% of their monthly income goes towards assisting relatives. Meanwhile, in South Africa, where unemployment exceeds 42%, a single wage typically sustains nearly four people, according to the Pietermaritzburg Economic Justice & Dignity Group.

Impact on Business and Economy

Research in Kenya indicates that the pressure to provide monetary aid to family can lead entrepreneurs to restrict their business growth. Despite this, remittances from Africans living outside the continent play a crucial role in sustaining households and aspirations, covering expenses from rent to healthcare and education fees. In 2022, these transfers totalled $100 billion (£74 billion), surpassing both aid and foreign investment, as reported by the African Development Bank.

Many highly educated young professionals pursue lucrative careers not only for personal gain but also to accumulate wealth for future generations, hoping to shield them from the hardships they endured during their own upbringing.

Personal Stories from the Diaspora

Kenya: A Lifelong Commitment

Anthony Kimere, a 55-year-old Kenyan, moved to Europe 36 years ago, studying and working in Italy before relocating to Germany, Denmark, and now the UK, where he drives buses for Transport for London. Over the decades, he has supported his extended family back home in various ways, including sending upkeep to his grandparents, covering school fees for a cousin, and contributing to medical bills for numerous relatives.

Kimere, who grew up in Timau, central Kenya, explained that he often feels a subconscious obligation to help due to his understanding of the challenges faced by his kin. 'You feel obligated to give back because you know the situation,' he said. 'You know your background, you know the people you have left behind, so you are quite aware of the difficulties they go through.' He acknowledged that assisting his large extended family sometimes strains his personal finances, noting, 'The more people there are, the more frequent problems might be.'

Zimbabwe: Building for the Future

Fungai Mangwanya, a 35-year-old data analyst from Zimbabwe, experienced hyperinflation and economic collapse during his youth. Witnessing his grandmother's struggles to make ends meet while raising him motivated him to seek a high-earning career. He moved to the UK in 2022 with his wife to support those who raised them and build wealth for future children.

'As you're getting into adolescence, you begin to see what's going on with the economy ... and you see how tough some areas are. So you begin to try and try and try and put yourself in that narrow band of people that have better opportunities,' Mangwanya shared. Despite the deaths of his grandmother and his wife's uncle last year, he continues to support his aunt, brother, and a cousin in university, aiming to ensure his future children have financial stability.

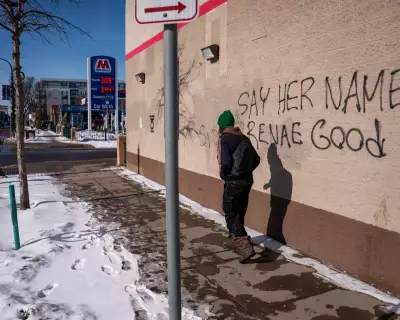

South Africa: Overcoming Inequality

Mpho Hlefana, a 37-year-old marketing professional from South Africa, achieved her goal of leading a marketing department before turning 40, yet she constantly worries about potential losses. Growing up in Soshanguve, a former black-only township near Pretoria, she was taught the value of education and hard work by her parents. After moving to the more affluent Queenswood suburb for better schools, she studied marketing at the University of Pretoria.

Although the end of apartheid in 1994 opened up opportunities, South Africa remains racially unequal, with average white household income nearly five times that of black households in 2023. Hlefana, now in Johannesburg, aims to build wealth to provide her daughters with homes and cars, echoing her parents' aspirations for her to do better.

Taxation and Ongoing Challenges

In some European countries and recently in the US, where a 1% remittance tax has been introduced, the financial strain on senders may increase. Eguono Lucia Edafioka, a Nigerian doctoral student at Vanderbilt University, emphasised that remittances often cover essential needs like food and medicine, leaving little choice for senders.

Experts caution that such taxes could disproportionately affect lower-income migrants, who already face high transaction fees. Abednego Kwame, a 32-year-old Ghanaian management consultant in New Jersey, budgets for these transfers and notes that his family is understanding of any reductions due to taxes.

Overall, the 'black tax' remains a complex interplay of duty, sacrifice, and aspiration, shaping the lives of African workers and their families across the globe.