Fifteen years after the catastrophic Fukushima Daiichi meltdown, Japan stands on the brink of a controversial energy milestone: the restart of the world's largest nuclear power station. The Kashiwazaki-Kariwa plant in Niigata prefecture, dormant since 2012, could see one of its seven reactors brought back online imminently, reigniting a fierce national debate over safety, memory, and energy policy.

A Colossal Facility and a Contentious Comeback

Sprawling across 4.2 square kilometres on Japan's Sea of Japan coast, the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa facility is a behemoth of atomic energy. When operating at full capacity, its seven reactors can generate a staggering 8.2 gigawatts of electricity, enough to power millions of homes. Today, the site is a hive of final preparatory activity, with roadworks and a formidable security presence of razor-wire fences and patrols underscoring the high stakes.

Operated by Tokyo Electric Power (Tepco)—the same utility behind the Fukushima plant—Kashiwazaki-Kariwa has been idle for over a decade. It was shut down alongside dozens of other reactors nationwide following the March 2011 triple meltdown, triggered by a tsunami that overwhelmed the Fukushima plant's defences. That disaster forced 160,000 people to evacuate and stands as the world's worst nuclear accident since Chernobyl.

The planned restart of reactor No. 6 is a cornerstone of the Japanese government's revived nuclear strategy. Officials argue that returning to atomic power is essential for meeting emissions targets and bolstering national energy security. Before 2011, 54 reactors supplied about 30% of Japan's electricity; today, only 14 of 33 operable units are running.

"Everything" to Fear: Local Opposition and Evacuation Anxieties

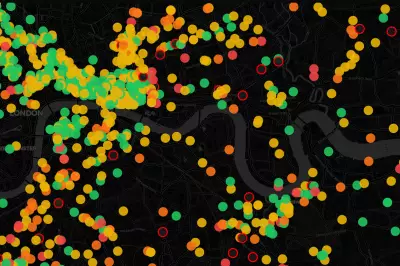

For the 420,000 residents living within a 30km radius of the plant, the restart is not a policy abstract but a profound safety concern. Their fears are rooted in geography, demography, and recent history.

Ryusuke Yoshida, a 76-year-old potter whose home lies less than 1.5 miles from the plant in Kariwa village, summarises local apprehension in one word: "Everything." He points to the glaring practical flaws in evacuation plans for a region prone to heavy winter snows and with a large elderly population. "The evacuation plans are obviously ineffective," Yoshida states. "When it snows in winter the roads are blocked... This is a human rights issue."

These concerns are amplified by the area's seismic profile. The plant itself sustained damage during a 6.8-magnitude offshore earthquake in 2007, and active faults are known to be in the vicinity. Furthermore, the nuclear industry's credibility was recently dented by a scandal at the Hamaoka plant, where a utility admitted to fabricating seismic risk data.

Kazuyuki Takemoto, a 76-year-old member of the Kariwa village council, is scathing. "It used to be said that nuclear power was necessary, safe and cheap … We now know that was an illusion," he says, criticising the lack of meaningful public discussion on safety guarantees.

Tepco's Safety Pledges and an Unconvinced Public

Tepco insists it has absorbed the harsh lessons of Fukushima. The company spokesperson, Tatsuya Matoba, states that "the core of the nuclear power business is ensuring safety above all else." The utility has invested in substantial upgrades at Kashiwazaki-Kariwa, including enhanced seawalls, watertight doors, mobile generators, and filtered venting systems to control radioactive releases.

In a bid to win local support, Tepco has also pledged to invest 100 billion yen (approximately £470 million) into Niigata prefecture over the next decade. However, this financial gesture has done little to sway public opinion, especially after local authorities rejected calls for a prefectural referendum on the plant's future.

A late 2023 survey by the prefectural government revealed that over 60% of locals within 30km did not believe the conditions for a restart had been met. Matoba acknowledges the company takes this result "very seriously," framing trust-building as "an ongoing process with no end point."

For campaigners like Yoshida, the restart represents the enduring power of Japan's "nuclear village"—the alliance of industry, regulators, and government. "The local authorities have folded in the face of immense pressure from the central government," he claims. "The priority of any government should be to protect people's lives, but we feel like we have been deceived."

As Japan marks 15 years since a tsunami killed an estimated 20,000 people and triggered the Fukushima meltdown, the restart of Kashiwazaki-Kariwa is a high-stakes gamble. It tests the nation's faith in its reformed nuclear safeguards against the visceral, unresolved fears of those who live in the shadow of the world's most powerful atomic plant.