Ofgem's Capital Target Failures Rise as Energy Suppliers Struggle

The energy regulator Ofgem has disclosed that an increasing number of retail energy suppliers are failing to meet their capital targets, raising fresh concerns about financial resilience in the sector. According to a recent report, five suppliers were below their required capital levels at the end of September, up from three in June last year. With only 23 suppliers operating at the time, this represents slightly more than a fifth of the supplier base falling short of regulatory standards.

Background to the Capital Target Regime

The introduction of capital targets by Ofgem in March last year was a direct response to the catastrophic failures during the gas crisis of 2021-22. During that period, half of the nation's retail energy suppliers collapsed, including Bulb with 1.7 million customers. The National Audit Office estimated the cost of these corporate calamities at £2.7 billion, equating to an additional £94 on every household's energy bill. Ofgem's new regime aims to ensure suppliers maintain sufficient financial buffers to withstand market shocks.

Current Financial Resilience Concerns

The timing of these capital target failures is particularly concerning given the renewed volatility in wholesale gas prices. While not yet at the extreme levels seen in 2021-22, cold weather in North America has disrupted European markets, potentially affecting UK suppliers' hedging arrangements. This volatility underscores the importance of robust capital positions to protect consumers and maintain market stability.

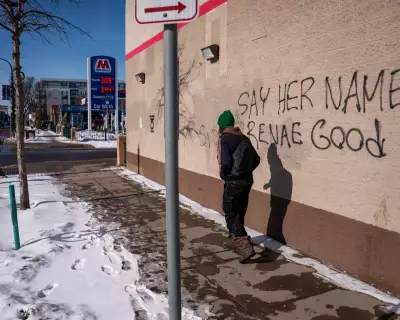

Ofgem's report states: "Where suppliers are below the target, we work proactively with them on their plan to meet this target in the shortest reasonable time." However, the regulator provides limited transparency about these plans. It does not name the under-target firms—though Octopus and Ovo voluntarily disclosed their status last year—nor does it specify how far they fall short of the £115 per dual fuel equivalent customer target.

Regulatory Transparency Issues

The lack of detail in Ofgem's approach has drawn criticism from industry observers. Key questions remain unanswered:

- What constitutes "the shortest reasonable time" for compliance—six months, a year, or longer?

- How does Ofgem define "working proactively" with suppliers?

- What makes a capital-improvement plan "credible and agreed"?

Ofgem defends its opacity by citing commercial sensitivity, but this stands in stark contrast to practices in other regulated sectors. For instance, the Bank of England publishes detailed stress test results for banks, which are scrutinised by financial markets. Banks face severe consequences even for approaching regulatory minimums, creating a clear deterrent against undercapitalisation.

Industry Reactions and Regulatory Pressure

The debate over Ofgem's enforcement approach has been lively. Centrica, owner of British Gas, has been particularly vocal, with its chief executive previously describing the situation as "criminal" and advocating for immediate bans on under-target firms from taking new customers. While not everyone supports such drastic measures, there is growing consensus that Ofgem's current approach may be too lenient.

As the number of laggard suppliers increases, Ofgem faces mounting pressure to demonstrate that its "get-tough" regime has teeth. The regulator reserves the right not to explain what it considers credible compliance plans, but this lack of transparency undermines confidence in the system. With wholesale gas markets remaining unpredictable, the need for financially resilient energy suppliers has never been more critical.

The energy sector continues to watch closely as Ofgem navigates these challenges, balancing commercial sensitivities with the need to protect consumers from future market disruptions.