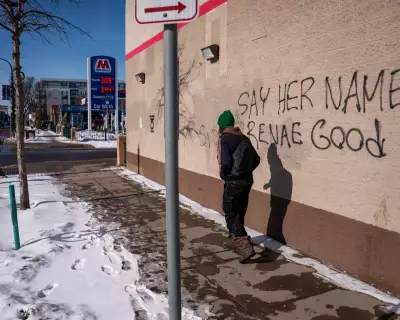

The image of cars being spray-painted at Jaguar Land Rover's advanced manufacturing facility in Solihull, Birmingham, in 2017 serves as a poignant reminder of Britain's industrial heritage. Yet, this scene contrasts sharply with the nation's current economic reality, where manufacturing has dwindled to a mere fraction of its former glory. As Britain grapples with post-industrial decline, crucial lessons can be drawn from China's remarkable economic transformation over recent decades.

The Great Economic Reversal: Britain and China's Divergent Paths

When Margaret Thatcher and Deng Xiaoping assumed power within months of each other in the late 1970s, both leaders embarked on ambitious economic missions. Thatcher sought to reinvigorate British capitalism through market liberalisation, while Deng launched his programme of "socialism with Chinese characteristics" aimed at modernising China's peasant economy. The subsequent decades witnessed a dramatic reversal of fortunes between the two nations.

China has evolved from an agricultural society into a global industrial powerhouse, dominating sectors from electric vehicles to artificial intelligence. Meanwhile, Britain has seen its manufacturing base shrink dramatically, becoming a service-sector dominated economy where finance reigns supreme. This transformation has created an economic landscape where services now account for approximately 80% of Britain's economic output, dwarfing manufacturing's contribution tenfold.

Three Crucial Lessons from China's Manufacturing Success

The first and most fundamental lesson is that manufacturing genuinely matters for national prosperity. Britain cannot achieve sustainable economic growth without rebuilding its productive capabilities. The alternative to a robust manufacturing sector isn't an economy filled with highly paid knowledge workers, but rather a low-tech service economy where productivity improvements prove exceptionally challenging.

Britain's persistently weak productivity performance since the 2008 financial crisis stems directly from this structural imbalance. Services depend fundamentally on manufactured goods - from machinery and transport systems to data infrastructure and energy equipment. When a nation ceases to manufacture these essentials, it becomes dependent on imports, creating persistent trade deficits that Britain has experienced since the early 1980s.

The Path to Industrial Renaissance

The second crucial insight is that Britain's industrial decline isn't irreversible. Despite fifty years of manufacturing erosion, Britain remains a wealthy nation with substantial untapped talent and resources. The success of Denmark's wind-turbine industry demonstrates that small, affluent Western nations can still achieve industrial excellence. Pessimistic assumptions that Britain's manufacturing era has permanently ended ignore the nation's remaining industrial strengths in sectors like pharmaceuticals and its potential for renewal.

The third lesson acknowledges the scale of challenge involved. Revitalising British manufacturing requires monumental effort and sustained commitment. Even raising manufacturing's share of the economy from 8% to 10% of GDP would represent a significant achievement, requiring industrial strategies that persist beyond political cycles and withstand Treasury scrutiny.

Practical Strategies for Manufacturing Revival

Britain faces immediate practical challenges in rebuilding industrial capacity. New manufacturing ventures risk being overwhelmed by established international competitors, particularly in sectors like electric vehicles where Chinese manufacturers offer aggressively priced alternatives. Overcoming these obstacles requires proactive government intervention of the sort regularly employed by developing economies.

Potential measures include domestic content requirements for goods sold in Britain, "buy British" procurement policies for public projects, manufacturing subsidies, and targeted tax credits similar to those introduced in the United States. These protective measures, commonly used by developing nations to nurture infant industries, could provide British manufacturing with the breathing space needed to establish competitive footing.

China's continued use of industrial policy, capital controls, and strategic support for key sectors demonstrates that even the world's second-largest economy recognises the value of targeted intervention. For Britain to escape its post-industrial malaise, adopting similar strategic approaches could prove essential. Ultimately, rebuilding British manufacturing requires viewing economic challenges through the lens of a developing nation rather than a developed one, embracing proactive industrial policies that prioritise long-term productive capacity over short-term market efficiency.