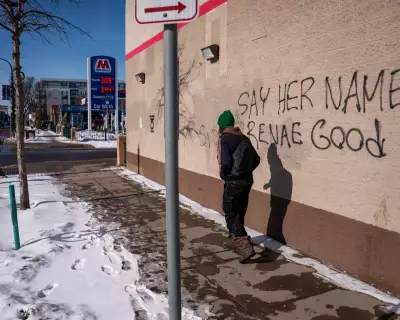

Since 2021, China has reportedly directed a staggering $100 billion into supporting artificial intelligence datacentres across the nation. This massive financial commitment underscores Beijing's determination to become a global leader in AI technology, though experts note the country currently lags behind the United States at the cutting-edge frontier of artificial general intelligence.

Corporate Visions vs National Strategy

In a significant departure from his normally reserved public persona, Alibaba CEO Eddie Wu captured international attention with a bold speech in September. Addressing a developer conference in Hangzhou, Wu declared the dawn of an "AI-driven intelligent revolution" and announced plans to invest 380 billion yuan (approximately £40 billion) in AI infrastructure over the next three years.

"Artificial general intelligence will not only amplify human intelligence but also unlock human potential, paving the way for the arrival of artificial superintelligence," Wu proclaimed, suggesting ASI could create "super scientists" and "full-stack super engineers" capable of solving complex problems at unprecedented speeds.

This visionary rhetoric, reminiscent of statements from Western tech leaders like OpenAI's Sam Altman, marked what technology writer Afra Wang described as a breakthrough moment where "major Chinese companies are beginning to articulate their own grand visions that carry the flavour of future prophecy."

The American Perspective on the AI Race

Across the Pacific, American officials have framed the competition in existential terms. Microsoft President Brad Smith told a US Senate committee that "the race between the United States and China for international influence likely will be won by the fastest first mover." This perspective has gained traction in Washington, where the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission has recommended Congress establish a "Manhattan Project-like program" dedicated to achieving AGI capability.

China's Pragmatic AI Approach

Despite Alibaba's ambitious pronouncements, most Chinese AI companies and the government itself maintain a more practical focus. Ya-Qin Zhang, dean of Tsinghua University's Institute for AI Industry Research, observed that "most AI companies are working towards better applications" rather than pursuing AGI directly.

This pragmatic orientation is reflected in China's official "AI+ strategy" published in August, which outlines how artificial intelligence can accelerate development goals in healthcare, supply chains, and other sectors without mentioning AGI at all.

Julian Gewirtz, former senior director for China and Taiwan at the White House National Security Council, noted: "The Chinese government is intently focused on reaping the benefits of AI in the here and now and in the near future through diffusion and application of AI across the economy, society, defence, and other areas."

The Semiconductor Challenge

One significant factor shaping China's AI strategy is Washington's ban on exporting advanced microchips to Chinese companies. These sophisticated semiconductors are essential for cutting-edge AI research, forcing Chinese firms to rely on less efficient domestic alternatives or specially developed Nvidia chips for the Chinese market.

In December, Washington approved the sale of Nvidia's H200 chips to China, but Beijing reportedly instructed customs agents to block their importation as part of efforts to reduce dependence on foreign technology. This technological constraint means most Chinese companies find it more profitable to focus on AI applications using existing hardware rather than pursuing AGI research.

Datacentre Development and Energy Concerns

The competition extends beyond chips to include datacentre infrastructure and energy resources. Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang suggested in November that China could "win the AI race" partly due to government energy subsidies for datacentres.

These subsidies reportedly emerged after Chinese tech companies complained about higher electricity costs resulting from using less efficient domestic semiconductors. In a clear signal of Beijing's determination to promote homegrown technology, Reuters reported that datacentres receiving state funding must exclusively use domestic chips.

However, this rapid expansion has led to concerns about overcapacity. A report from the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology revealed that nationwide utilisation rates for AI datacentres stand at just 32%. Rao Shaoyang, director at the China Telecom Research Institute, warned against "blindly building intelligent computing centres" and urged consideration of local computing demand before constructing new facilities.

A Fluid Competitive Landscape

Despite current limitations in computing power and semiconductor technology, analysts caution against assuming China's AI strategy will remain static. Gewirtz observed: "The current status quo is highly fluid, and Xi Jinping has explicitly declared an ambition to lead the world in AI. So the fact that China construes that goal one way at this snapshot moment in time does not give me any comfort that in a year they're going to construe it the same way."

While companies like DeepSeek, whose founder Liang Wenfeng has expressed interest in AGI, demonstrate China's innovative potential, the nation's AI development currently prioritises practical applications over theoretical frontiers. This approach reflects both technological constraints imposed by US sanctions and a philosophical preference for tangible economic benefits over speculative technological achievements.

As the global AI competition intensifies, China's $100 billion investment in datacentre infrastructure represents a significant commitment to technological advancement, even as the country navigates complex challenges in semiconductor development, energy management, and strategic direction between immediate applications and future AGI possibilities.