Concerns are intensifying among analysts that the staggering investment fuelling the artificial intelligence revolution may be inflating a dangerous financial bubble. The dominance of AI stocks in the US market, coupled with astronomical spending that vastly outstrips current profits, is raising alarm bells about a potential correction.

The Trillion-Dollar Bet: Spending Versus Returns

The market's appetite for AI remains voracious. While some key players like Nvidia, Oracle, and Coreweave have seen valuations dip from mid-2025 highs, the US stock market is still overwhelmingly driven by AI investment. A remarkable 75% of returns from the S&P 500 index are attributed to just 41 AI-related stocks. The so-called "Magnificent Seven" tech giants—Nvidia, Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Meta, Apple, and Tesla—alone account for 37% of the index's performance.

This concentration, built largely on one form of AI—Large Language Models (LLMs)—is fuelling bubble fears. AI leaders dismiss such talk. Jensen Huang, CEO of the now $5 trillion chip-maker Nvidia, stated last month, "We are long, long away from that."

However, scepticism persists. The colossal gap between expenditure and revenue is testing investor nerves. Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Meta, and Oracle are projected to spend around $1 trillion on AI by 2026. OpenAI, the creator of ChatGPT, plans to commit a staggering $1.4 trillion over the next three years.

The returns so far are minimal by comparison. OpenAI is expected to generate just over $20 billion in profit for 2025—a vast sum, but a fraction of its planned outlay. "If a few venture capitalists get wiped out, nobody's gonna be really that sad," said AI scientist Gary Marcus, an emeritus professor at New York University. "But with a large part of US economic growth this year down to investment in AI, the 'blast radius' could be much greater."

The Physical Crunch: Power, Chips, and Depreciation

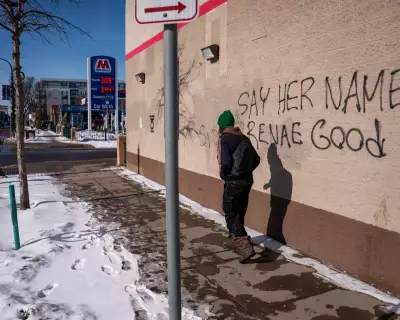

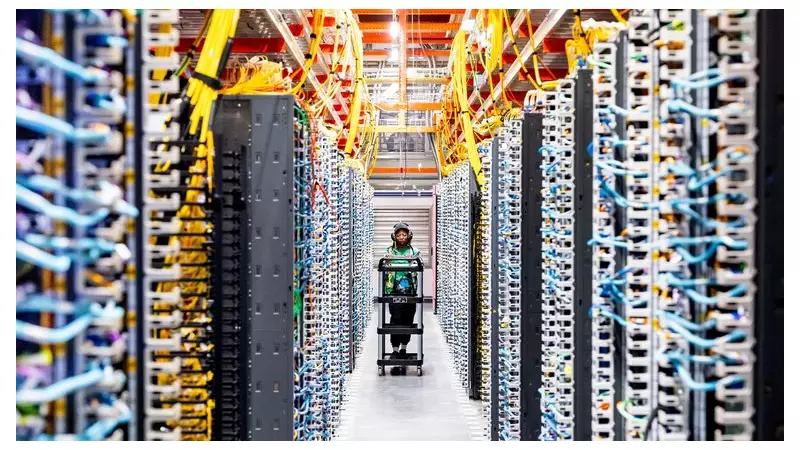

The AI boom's scale hinges on immense physical infrastructure, creating several unique pressure points. The leap in capability from GPT-2 to GPT-4 required 3,000 to 10,000 times more computing power, triggering a race to build "computer cities." Projects like the Stargate complex in Texas and Meta's $27 billion Hyperion data centre in Louisiana are consuming land areas comparable to major city parks or even Manhattan itself.

This is straining America's power grid, with some data centres facing years-long waits for connections. Furthermore, unlike traditional infrastructure, AI data centres face rapid obsolescence. Nvidia releases new, more powerful AI chips roughly every year, claiming a three-to-six-year lifespan for its latest models.

Fund manager Michael Burry, famed for predicting the 2008 crash, is now betting against AI stocks, citing fears chips may need replacing every three years or sooner due to competition. The Economist recently estimated that if AI chips depreciate every three years, it could wipe $780 billion from the combined value of five big tech firms. If the cycle shortens to two years, that loss balloons to $1.6 trillion.

The Adoption Gap: Where Are the Profits?

The fundamental question remains: who will pay enough for AI to justify trillion-dollar investments? While adoption is rising—OpenAI reports 800 million weekly active users—only 5% are paying subscribers. Business adoption, the key revenue source, is sluggish. US Census data from early 2025 showed only 8-12% of companies using AI to produce goods and services. For larger firms, adoption peaked at 14% in June 2025 but has since fallen back to 12%.

Most companies are still piloting AI or figuring out how to scale it. Compounding this is growing doubt about the core "scaling hypothesis." While LLMs improve on technical benchmarks, their fundamental architecture lacks true understanding or long-term memory. Ilya Sutskever, co-founder of OpenAI, recently noted, "Is the belief that if you just 100x the scale, everything would be transformed? I don't think that's true."

Professor Marcus summarises the precarious equation: "It's really just a scaling hypothesis, a guess that this might work. It's not really working. So you’re spending trillions of dollars, profits are negligible and depreciation is high. It does not make sense. And so then it's a question of when the market realises that." The wait for that realisation is keeping investors and analysts on edge.