Across Britain's bustling high streets, a quiet revolution is unfolding in the ancient art of henna. What was once confined to wedding ceremonies and family gatherings has exploded into mainstream consciousness, driven by a new generation of artists reclaiming this traditional practice as a powerful form of self-expression.

From Eid Celebrations to Red Carpets

The night before Eid now sees plastic chairs lining pavements from London to Bradford, where women sit elbow-to-elbow beneath shopfronts, hands outstretched as artists swirl cones of henna into intricate patterns. For just £5, pedestrians can walk away with both palms blooming in temporary botanical gardens.

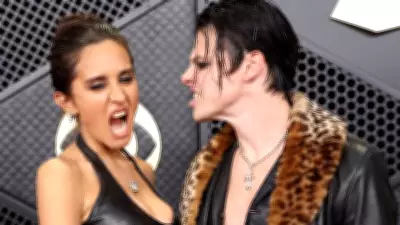

This centuries-old ritual has dramatically evolved from private living rooms to very public spaces, and today it's being completely reimagined. In recent years, henna has made the journey from family homes to international red carpets – from actor Michaela Coel's Sudanese motifs at the Toronto film festival to Katseye singer Lara Raj's henna decoration at the 2025 Video Music Awards.

The digital world has amplified this transformation. UK searches for henna reportedly skyrocketed by nearly 5,000% last year, while social media platforms overflow with everything from henna-created faux freckles to five-minute floral design tutorials, demonstrating how this natural dye has adapted to contemporary beauty culture.

Reclaiming Cultural Identity Through Art

For many British people of colour, the relationship with henna hasn't always been straightforward. Many recall childhood experiences of wearing fresh henna for special occasions, only to face questions from classmates and strangers who didn't understand the tradition. Some were asked if siblings had scribbled on them, while others faced comments about frostbite when their nails were decorated.

Now, a significant cultural shift is underway. Young people are returning to henna with renewed pride, using it as both cultural affirmation and political statement. This movement towards reclaiming henna from cultural erasure and appropriation resonates strongly with collectives like HuqThat, a six-member artist group based in London that's redefining henna as a legitimate art form.

"There's been a cultural shift," explains Ruqaiyyah Patel, who joined HuqThat two years ago. "People are really proud nowadays. They might have dealt with racism, but now they are coming back to it."

The Ancient Roots Meet Modern Expression

Henna's history stretches back more than 5,000 years, with the dye derived from the Lawsonia inermis shrub colouring skin, fabric and hair across Africa, south Asia and the Middle East. Early traces have even been discovered on Egyptian mummies. Known variously as mehndi, ḥinnāʾ, or lalle depending on region, its traditional uses range from cooling the body to dyeing beards and blessing newlyweds.

"Henna is for the masses," Patel emphasises. "It comes from working people, from villagers who grow the plant." Her colleague Nuzhat El Agabani adds their ambitious goal: "We want people to understand henna as a legitimate art form, just like calligraphy."

The collective's work has appeared at fundraisers for Palestine and Sudan, as well as Pride events, consciously creating inclusive spaces. "We wanted to make it an inclusive space for everyone, especially queer and trans people who might have felt excluded from these traditions," El Agabani explains. "Henna is such an intimate thing – you're entrusting the artist to look after part of your body. For queer people, that can be stressful if you don't know who's safe."

Global Perspectives, Personal Connections

Across the Atlantic, Aminata Mboup, an industrial designer and sculptor based in Toronto and Dakar, finds that fuddën (henna in Wolof) connects her to her Senegalese heritage. She uses jagua, a natural dye from the jenipapo fruit that stains a deep blue-black, reminiscent of her grandmother's darkened fingertips.

"When I wear it, I feel as if I'm stepping into womanhood, a sign of grace and elegance," Mboup shares. She now frequently wears henna in her daily life, describing it as performing her Blackness every day. "I have a sign of where I'm from and who I am right here on my hands, which I use for everything, every day."

Back in London, Pavan Ahluwalia-Dhanjal, founder of the world's first henna bar in Selfridges and holder of two Guinness World Records for fastest henna application, recognises its multiple meanings. "People use it as a political thing, a cultural thing, or just for beauty – and I respect all of that," she says.

Her journey wasn't initially met with support. "No one took me seriously, not even my own culture," she recalls. When she appeared on Dragons' Den in 2024, she was told henna wouldn't go beyond her community. "But for the first six years, most customers weren't from my culture at all."

Today, her henna bar employs 25 professional artists who conduct workshops across the UK and travel to Los Angeles. She envisions henna becoming "as accessible as lipstick or nail polish," calling it a "beauty staple" that's consistently sold throughout the year rather than just for special occasions.

As henna gains mainstream visibility, the conversation around cultural appreciation versus appropriation continues. Yet across continents and generations, henna's significance deepens and evolves. For artists and wearers alike, it represents both personal expression and cultural continuity – a temporary stain that leaves a permanent mark on identity and community.