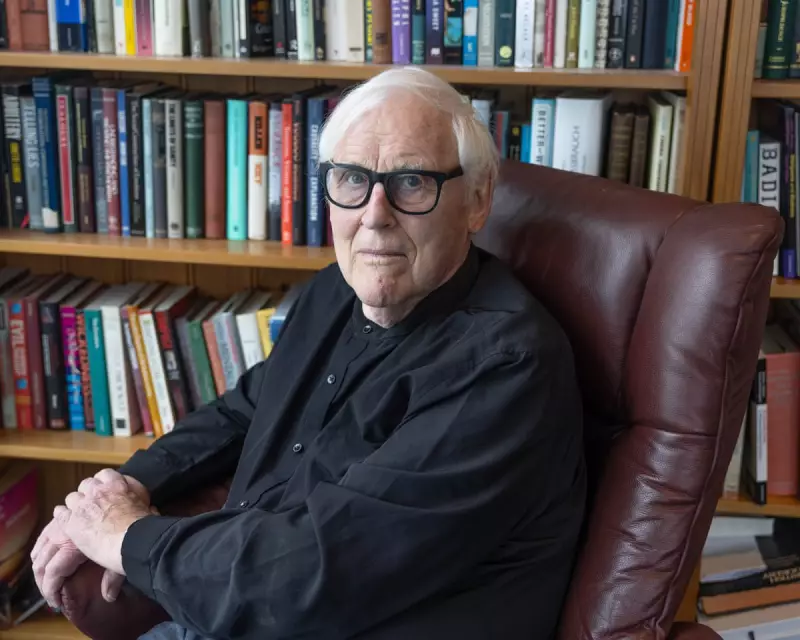

For over three decades, distinguished forensic psychiatrist Dr Paul E Mullen has conducted unprecedented research into one of society's most disturbing phenomena: the lone mass killer. His new book, Running Amok: Inside the Mind of the Lone Mass Killer, distills this extensive experience into a crucial examination of how these tragedies unfold - and how we might prevent them.

From Personal Tragedy to Professional Mission

Dr Mullen's journey into this dark territory began unexpectedly in November 1990. Living near Dunedin, New Zealand with his family, he heard distant gunfire one evening that would change the course of his career. The shooting continued through the night, accompanied by emergency vehicle sirens.

By 9pm, he learned the horrifying truth: a gunman had begun shooting people in the nearby settlement of Aramoana, just kilometres from his home. Mullen discovered he had connections to both the perpetrator and victims through his medical practice.

"I'd never really thought about these things," Mullen recalls. "They had never been on my radar." The Bristol-born psychiatrist had previously dabbled in forensic work, but the Aramoana massacre ignited a professional transformation that would see him become one of the world's leading authorities on mass violence.

Face to Face with Notorious Killers

Just six years after Aramoana, Mullen found himself summoned to Royal Hobart hospital following the devastating Port Arthur massacre in April 1996. The perpetrator had shot 55 people, killing 35, and was being treated for burns after setting fire to a guesthouse during his final confrontation with police.

Authorities had cleared the entire hospital floor and strapped the 28-year-old man to his bed. While media outside described him in terms like "evil" and "monster", Mullen approached him differently - as a "person who has killed" rather than simply a "killer".

"I thought it was going very well, until suddenly, blam, he says: 'I've got the record, haven't I?'" Mullen recalls. The comment revealed something crucial: despite his solitary actions, this killer was acutely aware of his place in a grim historical context.

Mullen soon discovered the man knew considerable details about previous massacres, establishing a pattern that would repeat across Mullen's decades of research. These apparently "lone" actors were actually deeply connected to a cultural narrative of previous mass killers.

The Emergence of a Deadly Cultural Script

Mullen's research traces the evolution of what he terms the "cultural script" for mass killings. The first similar incident in the Western world occurred in Germany in 1913, when a schoolteacher killed his wife and four children before travelling to Mühlhausen armed with several guns and hundreds of rounds of ammunition.

He killed nine people during his shooting spree, but Mullen notes this incident failed to create an enduring cultural script. "Between 1913 and 1966 there were three incidents, one was actually in Melbourne. But there was no cultural script created."

The turning point came in August 1966 with the University of Texas tower shooting. A 25-year-old male student climbed to the 28th-floor observation deck and opened fire, killing 15 people and injuring 30 others.

"He was in every major newspaper in America, on the front page the next day with his photograph and his name, and he was covered worldwide," Mullen explains. The subsequent 1975 film The Deadly Tower, starring Kurt Russell, further cemented this script in popular culture.

"It was the Texas university tower massacre that created the script, which has now grown and grown and grown," Mullen reflects. "And the first imitator of the Texas killer was only five weeks later."

Disrupting the Script: Practical Prevention Strategies

In Running Amok, Mullen outlines concrete strategies for interrupting these deadly patterns. He deliberately avoids naming modern perpetrators, instead focusing on victims' names and lives. Refusing to name killers is the "quickest, cheapest and easiest way" to reduce these events, he argues.

He also challenges the term "lone wolf", explaining that "this is exactly what they want to be seen as - the lone wolf, the predator going around the edges. They're not wolves. I mean, they're sheep."

Other crucial interventions include capturing perpetrators alive when possible, avoiding detailed reporting of their lives and manifestos, and preventing them from using courtrooms as platforms. These approaches directly counter their desires for infamy and a noteworthy death.

Mullen acknowledges the tension between public safety and principles like due process, transparency, and press freedom. The challenge has intensified with attention-driven media landscapes and unregulated online spaces that often sensationalise true crime.

The Human Reality Behind the Headlines

Despite spending his career studying those who commit unimaginable acts, Mullen maintains a nuanced perspective. "I mean, they're people," he reflects. "My job is to understand why they've done something extraordinary. Understanding doesn't mean forgiving. Understanding doesn't mean it's OK."

His research reveals that these individuals often struggle with uncertainty until the final moments. One perpetrator tossed a coin to decide his course of action, while the Port Arthur killer reportedly considered abandoning his plans if strangers would simply talk to him.

Rather than embodying pure evil, these crimes typically represent the convergence of predictable patterns and cultural scripts that can be interrupted before ending in tragedy. Mullen's work offers not just understanding, but hope - that by recognising and disrupting these scripts, we might prevent future violence.

Running Amok: Inside the Mind of the Lone Mass Killer by Paul E Mullen is available now through Extraordinary Books.