As approximately 40,000 delegates descend upon Belém, Brazil for COP30, the very nation that hosted the landmark Rio Earth Summit in 1992, fundamental questions about the effectiveness of these global gatherings are louder than ever. Despite nearly 30 rounds of UN climate negotiations, the natural world these summits pledged to protect is struggling for survival.

A Legacy of Hope and Hard Realities

The 1992 Rio Earth Summit was a historic moment, the largest gathering of world leaders ever seen at the time. It produced a suite of treaties, including the world's first global climate treaty, the UNFCCC, which promised to "protect the climate system for present and future generations." Michael Howard, Britain's environment secretary at the time, recalled an "atmosphere of hope" that this was the start of a process that could make a real difference.

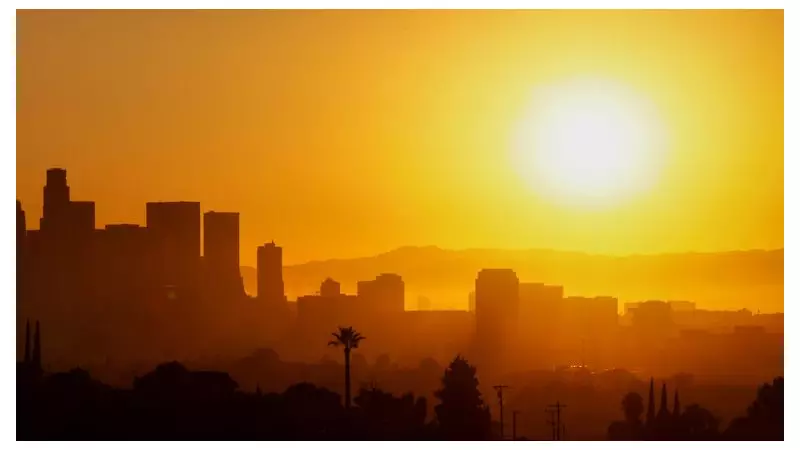

Yet, three decades on, the data paints a grim picture. Annual greenhouse gas emissions are now a staggering 65% higher than in 1990. Last year, the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere increased at its fastest rate on record. Global average temperatures have already climbed to approximately 1.4C above pre-industrial levels, dangerously close to the 1.5C limit aspired to in the Paris Agreement.

Measurable Progress Amidst Escalating Danger

This is not to say the COP process has been entirely fruitless. Defenders point to tangible, if insufficient, achievements. Before the Paris Agreement, the world was on track for a catastrophic 4C of warming by the century's end. Current projections, while still dire, sit at roughly 2.8C.

The Paris pact also catalysed a renewable energy revolution. This year, for the first time ever, renewables provided more electricity than coal. It also triggered a wave of net zero targets covering at least 77% of global GDP. Ed Miliband, the UK's Energy Secretary, called this "an absolute transformation" and stressed that international cooperation through COPs remains essential.

However, these gains are modest. Ian Hall, a climate professor at Cardiff University, warns these "limited signs of progress" are dwarfed by the scale and speed of change needed. The human cost is already devastating, with climate-related damage costing a colossal £1trn globally in 2024 alone, driven by more intense and frequent extreme weather.

A Process Under Scrutiny and Defence

The COP model itself is facing a crisis of confidence. A bombshell letter signed by figures like former UN chief Ban Ki-moon during last year's summit declared the conference "no longer fit for purpose," criticising its co-option by fossil fuel interests and unwieldy size.

Some, like Dr Jennifer Allan of Cardiff University, feel "complicit in the myth" that COP can save the world, citing its massive carbon footprint and repetitive debates. In response, UN climate chief Simon Stiell has assembled a team to explore reforms.

Yet, the loudest defenders are often the nations most vulnerable to climate impacts. For small island states like Palau, COP provides a rare platform to hold major economies accountable. Palau's president, Surangel Whipps Jr, stated, "If we don't come, there's nobody out there to defend the most vulnerable." He points to Australia's increased emissions target as direct proof of the process's influence.

As the world watches COP30 unfold in the threatened Amazon rainforest, the challenge is clear: move from "beautiful statements" to accountable action on promises already made. The future of multilateral cooperation, and the planet, may depend on it.