Sydney's Sewage Crisis: The 16-Month Battle Over Beach-Closing 'Poo Balls'

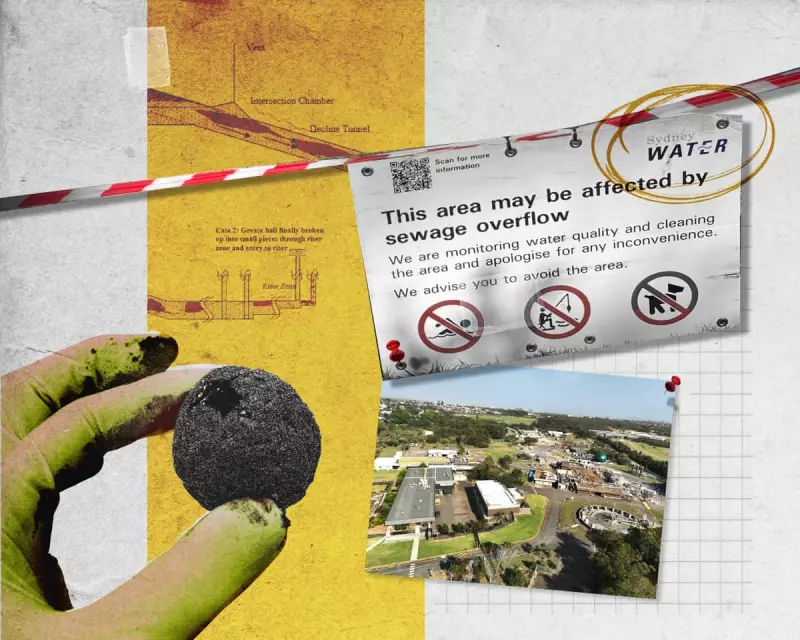

A colossal fatberg, measuring the size of four buses, has been identified as the likely source of the sewage debris balls that forced the closure of numerous Sydney beaches from October 2024 to January 2025. The problematic accumulation is located within Sydney Water's Malabar sewage treatment plant, specifically in an inaccessible dead zone between the Malabar bulkhead door and the decline tunnel.

Authorities Slow to Accept Responsibility

When mysterious debris balls first washed up on Coogee beach in October 2024, they were initially described as "tar balls" by authorities. Guardian Australia reported that scientists were investigating potential links to sewage outfalls as early as mid-October 2024, but Sydney Water pushed back strongly against this narrative. The corporation's media team attempted to have any reference to the organisation removed from related news coverage.

The Environment Protection Authority (EPA) reportedly knew the pollutant material was consistent with human-generated waste by 25 October 2024, but the official announcement that the balls were mini fatbergs containing human faeces wasn't made until 6 November 2024. This revelation coincided with US election coverage dominating news headlines, potentially minimising its impact.

Freedom of Information Battle Reveals Truth

It took a five-month freedom of information battle by Guardian Australia to finally narrow down the source in October 2025. The investigation confirmed what multiple experts had suggested: the debris balls were originating from deepwater ocean outfalls, specifically the Malabar outfall. Even during a briefing about the redacted report, Sydney Water and the EPA failed to disclose they had pinpointed the Malabar outfall as the specific source.

An oceanographic report commissioned by Sydney Water suggested the state-owned corporation could have known as early as 3 February 2025 that the debris balls were likely from its ocean outfalls. The final report was completed in late May 2025, but its findings weren't publicly acknowledged until much later.

An Intractable Engineering Problem

The August 2025 report on the deepwater ocean outfalls, handed to the EPA but never publicly released, reveals the serious and complex nature of the problem. According to the report, fats, oils and grease have accumulated in an inaccessible area of the Malabar system. Addressing the issue would require shutting down the 2.3km offshore outfall for maintenance and diverting sewage to "cliff face discharge," which would close Sydney's beaches for months.

This approach has "never been done" and is "no longer considered an acceptable approach," according to the report's acknowledgment. The deepwater ocean outfalls were originally opened from 1990 primarily because they represented the cheapest option when discharging sewage at the cliff face became untenable.

Funding Questions and Political Responses

When Guardian Australia began asking questions about the report before publication, Sydney Water and Water Minister Rose Jackson engaged in pre-emptive damage control. They announced a $3 billion "Malabar system investment program" to another media outlet, though this funding was not new money nor government funding. Instead, it was part of Sydney Water's existing $34 billion long-term capital and operational plan announced in September 2024.

The works outlined won't increase sewage treatment levels at Malabar, Bondi or North Head plants but aim to reduce the load heading to coastal facilities. Funding uncertainties persist, as the Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal (Ipart) has only approved a maximum 13.5% bill increase in the first year and 5% annually thereafter, including inflation, rather than Sydney Water's requested 53% over five years.

The 2025-26 NSW budget included no capital allocations for Sydney Water, noting the Ipart decision would come after budget delivery. Minister Jackson confirmed the government hadn't allocated taxpayer funding for the Malabar program, and sources indicate her request for government funding to expand Sydney's desalination plant has been rejected by the NSW treasurer.

As Sydney continues to grapple with this environmental and public health issue, the resolution will require significant political will and innovative engineering solutions to address a problem that has been developing for decades within the city's sewage infrastructure.