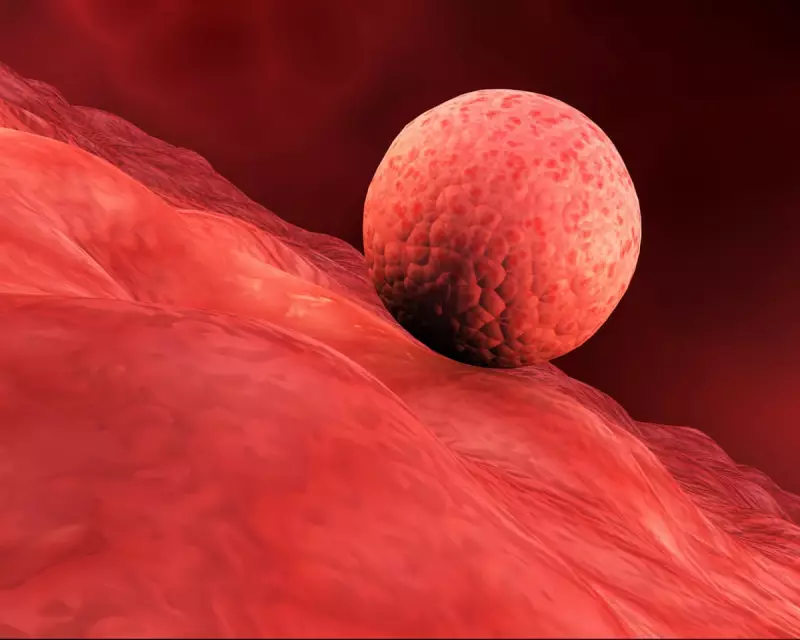

In a landmark scientific achievement, researchers have successfully engineered a replica of the human womb lining in a laboratory dish and used it to implant early-stage human embryos. This pioneering work promises to illuminate the enigmatic first weeks of pregnancy and the biological failures that can lead to miscarriage.

A Window into the Earliest Days of Life

The study, led by scientists at the Babraham Institute in Cambridge, involved creating a functional model of the uterine lining, known as the endometrium. The team built this structure using two key cell types donated from healthy women: stromal cells for structural support and epithelial cells that form the surface layer.

When early-stage human embryos, donated by couples after IVF treatment, were introduced to this engineered tissue, they attached and implanted as they would in a natural pregnancy. The embryos then began secreting crucial hormones, including human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) – the hormone detected by home pregnancy tests.

"It's incredible to see it," said Dr Peter Rugg-Gunn, the senior author of the study. "Previously we've only had snapshots of this critical stage of pregnancy. This opens up a lot of new directions for us."

Decoding the Chemical Conversation of Pregnancy

This novel technique allowed the researchers to observe embryos for up to the legal limit of 14 days post-fertilisation. Crucially, it enabled them to "eavesdrop" on the intricate molecular dialogue between the embedding embryo and the womb lining, a process vital for establishing a healthy pregnancy.

To demonstrate the model's power, the scientists blocked a specific signal between the embryo and the lining. This intervention caused severe defects in the developing placental tissue, highlighting how signalling problems can derail a pregnancy.

The research, published in the prestigious journal Cell, addresses a major gap in medical knowledge. Implantation occurs about a week after fertilisation but is notoriously difficult to study in humans. Much existing knowledge comes from historical studies of hysterectomies performed over half a century ago.

Transforming Fertility Treatment and Pregnancy Health

The implications of this breakthrough are profound. "We know that half of all embryos fail to implant and we have no idea why," stated Dr Rugg-Gunn. This new model provides a powerful tool to investigate those reasons, potentially leading to significant improvements in IVF success rates.

Furthermore, the system will allow scientists to study what happens immediately after implantation, when the placenta begins to form. Many serious pregnancy complications, such as pre-eclampsia, are thought to originate during this pivotal phase.

In a related study in the same journal, Chinese researchers used a similar model to identify drugs that might help patients with recurrent implantation failure (RIF), where high-quality IVF embryos repeatedly fail to result in a pregnancy.

Professor John Aplin, an expert in reproductive medicine at the University of Manchester, welcomed the findings. He noted that implantation rates in assisted reproduction have remained stubbornly low for decades. "This work will allow treatments to be explored that seek to improve implantation efficiency," he said.

This research marks a significant step towards unravelling the mysteries of human reproduction, offering new hope for understanding pregnancy loss and enhancing fertility care.