In an era where screens often replace faces, a leading neuroscientist is issuing a stark warning about the life-shortening effects of isolation and the profound health benefits of genuine human connection. Dr Ben Rein, a Stanford-trained researcher and science communicator, argues that socialising is not merely a pleasant pastime but a critical component of our wellbeing, influencing recovery from strokes, heart attacks, and even cancer.

The Loneliness Epidemic: A Silent Health Crisis

Dr Rein, who has amassed a significant following for debunking neurological myths online, is turning his attention to what he calls our "post-interaction world." His new book, Why Brains Need Friends: The Neuroscience of Social Connection, collates compelling evidence that isolation poses a severe threat to health. One particularly striking study he cites found that, among over 300,000 people, those with weaker social relationships had a 50% higher chance of dying within a seven-and-a-half-year period.

"It's horrifying," Rein admits during a video call from his home in Buffalo, New York. "But it's also like, why? How is that even possible?" To explain, he points to animal research. In studies where mice suffered identical strokes, those living alone fared dramatically worse, experiencing more brain damage, poorer recovery, and higher mortality rates. The culprit, it turns out, is a biological cascade triggered by solitude.

How Isolation Wreaks Havoc on the Body

Rein explains the mechanism with characteristic clarity. When we are isolated, our brain triggers a primal stress response, an evolutionary alarm bell signalling that being alone is dangerous. This leads to the release of the stress hormone cortisol. "Your body is preparing for a challenge," he says. Initially, cortisol suppresses inflammation to aid a potential fight-or-flight response.

The critical issue is that modern isolation is chronic, unlike a fleeting encounter with a predator. Under sustained stress, cortisol loses its anti-inflammatory effectiveness. "When you have this long-term, chronic stress response, it can lead to a buildup of inflammation," Rein states. This systemic inflammation, a key defence mechanism gone awry, taxes organs and impedes healing. In the mouse stroke study, when researchers suppressed the inflammation caused by loneliness, the isolated mice no longer suffered worse outcomes.

This translates directly to human health. Research shows heart attack patients living alone face double the risk of death in the following three years compared to those living with others. Conversely, stroke patients reporting high emotional support show "dramatic improvement" in functional capacity.

The Neurochemical Rewards of Friendship

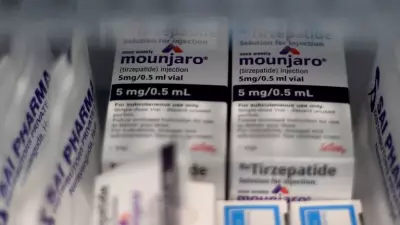

The flip side of this coin is the powerful benefit of connection. When we interact positively with others, our brains release oxytocin, which Rein dubs the "MVP of social bonding." This hormone is anti-inflammatory, suppresses stress, and promotes healing. Its effects are far-reaching: a 2013 study found married people, who typically have higher oxytocin levels, have better survival rates for cancer.

Evolution has hardwired us to seek this reward. Social interaction stimulates a potent cocktail of serotonin and dopamine. "Dopamine is the brain's way of saying what you're doing right now is good for you... serotonin is linked to mood," Rein explains. "The two together are incredibly powerful at making us feel good."

Yet, our brains often hold us back. We consistently underestimate how much we will enjoy socialising, undervalue our social skills, and believe others like us less than they do—a phenomenon known as the "liking gap." Rein attributes this social anxiety to an ancient need for cautious group navigation.

Upgrading Connection in a Digital Age

This innate caution is compounded by the poor substitute of online interaction. While digital communication surged during the pandemic, Rein warns it is a "pale imitation" for our brain's social reward systems, which thrive on facial expressions, vocal tone, and body language. He links the absence of these cues to increased online hostility and notes that social media users often report higher anxiety, depression, and loneliness.

His advice is simple: upgrade your interactions. Choose a phone call over a text, a video call over a phone call, and, wherever possible, meet in person. For those seeking a non-pharmaceutical oxytocin boost, getting a dog is highly effective—both species experience a rise in oxytocin during mutual gaze, and dog owners have lower cortisol and cardiovascular risks.

While Rein is an extrovert, he stresses there is no universal prescription. Both introverts and extroverts have different social needs, but everyone suffers from a lack of connection and benefits from its presence. His mission, ultimately, is pragmatic and idealistic. By framing social connection as a health imperative akin to sleep or vitamin D, he hopes to give people a personal incentive to engage—an act that, unlike going to the gym, also makes the world a slightly better place.