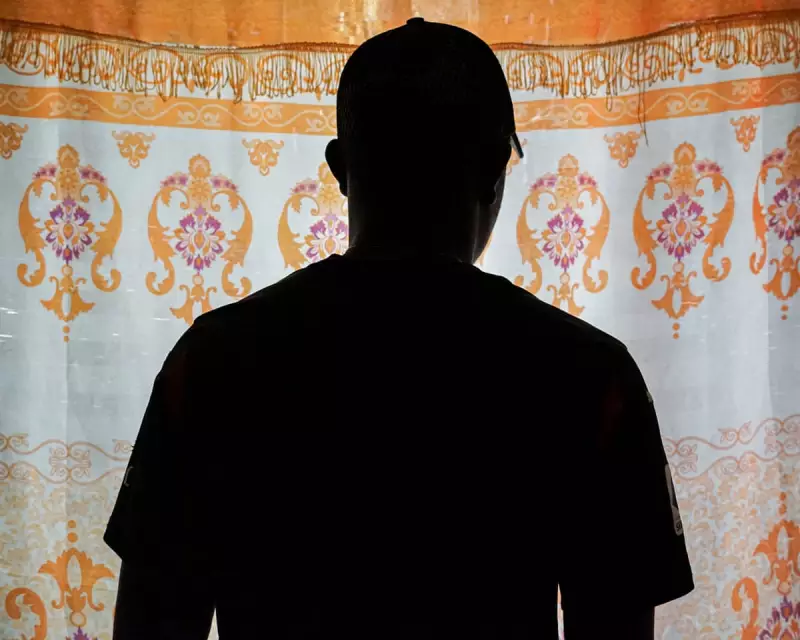

In a harrowing account of deception and survival, a Kenyan man who was trafficked to fight for Russia in its war against Ukraine has shared his story under a pseudonym after managing a daring escape. This exclusive revelation sheds light on a disturbing trend where African men are being lured by false promises of employment, only to find themselves on the frontlines of a brutal conflict.

The False Promise of a New Beginning

Stephen Oduor, a pseudonym used to protect his identity, was eagerly anticipating the start of his new role as a plumber in Russia, hoping to support his family after enduring months of unemployment. In August of last year, he travelled from Nairobi to St Petersburg alongside six other Kenyans, all enticed by the prospect of stable work abroad. However, suspicions arose almost immediately upon their arrival.

The individual who greeted them at the airport transported the group to a residence where their personal belongings were confiscated. They were then issued with black clothing and shoes before being escorted to a local police station. There, they were fingerprinted and compelled to sign documents written entirely in Russian, a language none of them could comprehend.

A Shocking Realisation

The following day, the group was taken to a substantial military facility within the city for the processing of military identification cards. It was at this moment that the 24-year-old Oduor began to understand the grim reality of his situation – he had been unknowingly enlisted into the Russian armed forces.

His fears were confirmed when he questioned one of the Russian officials about the purpose of the cards. Oduor recalls the man responding with chilling clarity: “You travelled all the way from Kenya and didn’t know what you were coming to do?” This marked the beginning of a terrifying ordeal that would see him thrust into a war zone without any prior military training.

From Civilian to Combatant

Oduor is one of more than 200 Kenyans, along with hundreds of other Africans, who have been trafficked to Russia under the guise of ordinary job opportunities. These individuals ultimately find themselves deployed to the frontline in Ukraine, facing extreme danger with little to no preparation.

After spending three days at the military facility, Oduor and his fellow Kenyans were placed on a train for a two-day journey to Belgorod, a city in south-western Russia near the Ukrainian border. At a military camp there, they were issued with uniforms, assault rifles, and other weaponry, and were immediately dispatched to the battlefield without any formal training.

“I didn’t know how to shoot anything,” Oduor admitted, reflecting on the perilous situation. For the subsequent three months, his primary duty involved shooting down Ukrainian weaponised drones. He would conceal himself for hours on end inside foxholes in forests across the border, listening intently for any signs of approaching drones. Each day of survival felt like a miracle, as being spotted by a drone would almost certainly result in a fatal strike.

Allegations of Racist Mistreatment and Strategic Recruitment

A growing number of individuals from African nations, including Kenya, Uganda, and South Africa, have been deceived into joining the conflict as Russia seeks to bolster its manpower. Late last year, Ukraine’s Foreign Minister, Andrii Sybiha, stated that over 1,400 citizens from 36 African countries were fighting for Russia in Ukraine, with many currently held as prisoners of war in Ukrainian camps.

Kenya’s Ministry of Foreign and Diaspora Affairs has acknowledged that more than 200 of its nationals may be in Ukraine, having been tricked by recruitment networks that post fraudulent job advertisements online. Recent footage circulating on social media appears to depict the dire conditions and racist mistreatment faced by Africans in Ukraine at the hands of Russian soldiers.

One video purports to show a Black man with an anti-tank mine strapped to his chest, being ordered at gunpoint in a trench to advance towards Ukrainian positions. A Russian speaker derogatorily refers to him as a “piece of coal” and indicates he will be used as an “opener” to detonate the mine and breach a Ukrainian bunker. Another video allegedly shows armed Black men in military attire singing a Ugandan revolutionary song in a snowy forest, while a Russian speaker in the background laughs and describes them as “disposables.”

While these videos remain unverified, they align with broader reports of Russia’s military tactics, which have included sending soldiers on what are effectively suicide missions. Testimonies from Russian troops have described being deployed as “mayachki” or “beacons,” ordered to march ahead of assault groups to draw enemy fire, often without adequate equipment.

Exploiting Economic Vulnerabilities

The recruitment networks, which include local employment agencies promising Kenyans foreign jobs, are capitalising on the country’s high youth unemployment rate and its initiatives to send citizens to work abroad. Denis Muniu, a security and foreign policy analyst, explained that these networks target unemployed youth qualified for general labour and infantry roles, as well as former security personnel who require minimal training. He highlighted the weak oversight of employment agencies as a key factor enabling this exploitation.

“It’s a very strategic way of recruiting these people,” Muniu noted. Neither Russia’s foreign affairs ministry nor its embassy in Nairobi responded to requests for comment, though the Russian government has previously denied involvement in schemes to recruit foreigners into its military. Kenya’s Ministry of Foreign and Diaspora Affairs also did not respond, but in a statement last month, it confirmed engagement with Russian and Ukrainian authorities in repatriation efforts.

A Bloody Escape and Lingering Trauma

Oduor’s path to freedom began with a near-fatal incident. One evening, while travelling in a pickup truck through a forest with three Russian soldiers en route to their night shift, he heard a sudden scream. Looking up, he saw a kamikaze drone heading directly towards them.

“I just saw death … I knew this was the end of us,” he recalled. The driver accelerated in an attempt to evade the drone, but within two minutes, it caught up and exploded. The passenger in the back seat was killed instantly, while Oduor and the driver sustained injuries from shrapnel. “We were lucky. God was with us,” he said of their survival.

After receiving initial treatment at a hospital in Belgorod, Oduor was transferred to facilities in Pskov. During his recovery, he secretly planned his escape, knowing he would be returned to the frontline once healed. By gaining the trust of a security guard through regular trips to a supermarket, he eventually seized an opportunity to take a taxi to the Kenyan embassy in Moscow, over 400 miles away. Embassy officials assisted him in obtaining an emergency passport for a flight back to Kenya.

Having sold his possessions to fund his relocation to Russia, Oduor returned home empty-handed and is now striving to rebuild his life on the outskirts of Nairobi. He underwent surgery to remove a shrapnel fragment and continues to recover, limiting him to light work. The psychological scars from his experience persist deeply.

“The experience seriously hurt me,” he confessed. “When you see someone dying and his head falling off, that disturbs you. It disturbed me a lot.”

Families Left in Anguish

Many Kenyans who have been trafficked to Ukraine have not been as fortunate as Oduor in returning home. Susan Kuloba has not seen her eldest son, David, since he departed for Russia in August. Employment agents had assured him of a security guard position, but instead, he was conscripted into the Russian military.

The 22-year-old, previously a construction worker in Nairobi, maintained contact with his mother via WhatsApp, sending messages, photos, and videos. On 30 September, the day before his second mission, he sent her a copy of his military contract and a distressing voice message hinting he might not survive.

He instructed her to contact Kenyan Immigration or the Russian embassy with his documents in the event of his death, promising a pay cheque. After three more days of communication, he fell silent. A week later, a friend of David’s who had escaped Russia informed Susan that her son had reportedly been killed, according to a WhatsApp group for Kenyan fighters.

For three months, Susan has sought answers, visiting and writing to the foreign affairs ministry, which only confirmed David’s arrival in Russia. The Russian embassy in Nairobi told her it does not handle military matters. “What hurts is I don’t know whether he’s dead or alive,” she expressed. “All I have is a claim by someone that he died, but I don’t believe it. But it’s been long. The government should just help us.”

This story underscores a grave humanitarian crisis, revealing how vulnerable individuals are being exploited through sophisticated trafficking networks, leaving families in despair and survivors grappling with profound trauma.