A lively debate has erupted in education circles following a letter to the Guardian which criticised a viral trend among schoolchildren. The trend in question involves pupils randomly saying the phrase 'six-seven' for no apparent reason, a behaviour branded by some as an 'embracement of idiocy'. However, a chorus of voices, particularly from within the teaching profession, has risen to defend the craze as a normal and valuable part of childhood.

The Educational Defence: Connection Over Correction

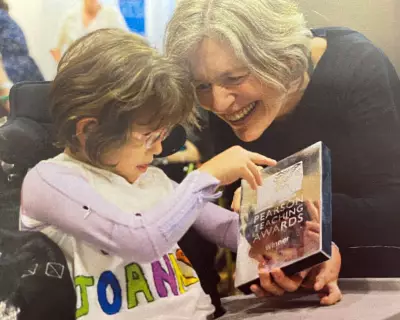

Leading the defence is teacher Alexsandro Pinzon from Mitcham, London. He argues that from a developmental perspective, such behaviour is not only normal but healthy. 'Children and young people often adopt shared phrases, jokes or nonsensical trends as a way of belonging to a group,' Pinzon writes. He emphasises that the meaning is often secondary to the act of participation itself.

For educators, understanding these trends is a powerful tool. Pinzon states that acknowledging this behaviour helps teachers connect with pupils' lived realities. 'When students feel seen and understood – rather than dismissed for engaging in harmless trends – trust is built,' he explains. This foundation of trust and connection is, he contends, crucial for effective learning, making pupils more likely to engage and take intellectual risks.

A History of Nonsense: From Dadaism to 'Bogeys'

Other correspondents were quick to point out that such fads are far from new. Ted Watson from Brighton recalls similar behaviour from his own 1960s childhood, such as an entire class placing spread fingers on their heads when a teacher entered the room. He draws a parallel between the children's actions and the artistic movements of surrealism and Dadaism, which embraced the illogical and nonsensical as a form of expression.

Torran Turner from Littleborough, Greater Manchester, references other generational touchstones of absurd humour, from Dick and Dom's loud cries of 'bogeys' to the simple hilarity of the word 'pants'. His plea is simple: 'Let people have nice things.' He warns that by 'pooh-poohing' such trends from on high, adults risk telling children their joy is wrong, thereby 'stealing a little bit of their childhoods'.

The Core Argument: Intelligence Isn't Opposed to Fun

The central thesis uniting these responses is a rejection of the idea that silliness equates to stupidity. Alexsandro Pinzon puts it succinctly: 'Harmless humour does not indicate a lack of intelligence.' He agrees that teaching critical thinking and self-reflection remains vital, but this should coexist with an understanding of the social and emotional role of play.

He concludes that hope in schools is fostered not just through kindness and honesty, but through 'laughter, shared experiences and relationships built on mutual respect'. Allowing space for these ostensibly trivial moments, he argues, ultimately strengthens the learning environment rather than undermining it.

Amidst the discussion, Mike Hine from Kingston upon Thames offered a tangential linguistic critique, questioning the inflation of the term 'student' to describe primary schoolchildren rather than those in further or higher education.