A slip on the ice at the start of the new year resulted in a broken right wrist for Guardian columnist Polly Toynbee, rendering her writing hand useless. Her subsequent trip to Accident and Emergency, however, became an unexpected case study in public perception versus statistical reality.

The Calm Before the Cast

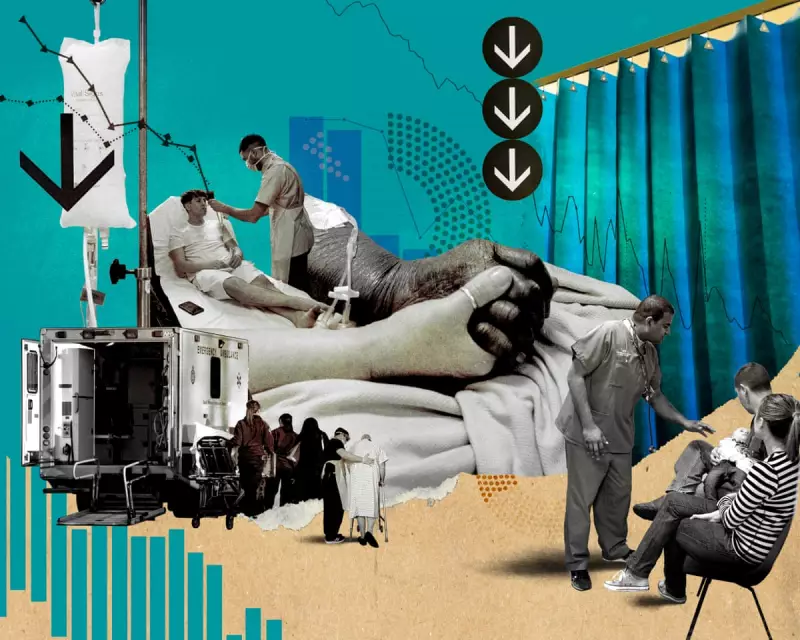

Bracing for the widely reported 12-hour waits and corridors choked with trolleys, Toynbee entered her local A&E department prepared for the worst. The atmosphere she encountered was strikingly different. The waiting area was hushed, with around 25 calm patients. Notices warned of zero tolerance for abuse against staff, a pertinent warning given that recorded violent incidents in English NHS trusts rose from 91,175 in 2022-23 to 104,079 in 2024-25.

Her treatment was swift. Within half an hour she was sent for an X-ray, and in under an hour a doctor confirmed the break. The medic, finishing a 12-hour shift after applying his 19th plaster cast of the day, expertly set the wrist, consulted specialists, and booked a follow-up. The initial reaction was one of relief: How lucky I was.

The Statistics Behind the Sentiment

Upon reflection, Toynbee questioned this notion of luck. As someone who has long tracked NHS performance data, she examined the figures. The latest statistics show that while the longstanding 95% target for four-hour treatment is badly missed, 73.9% of patients in England are still seen within that time. Her experience, therefore, was statistically ordinary, not exceptionally fortunate.

Similarly, the fear of disorder was not borne out. A Royal College of Nursing report highlighted that A&E staff are attacked roughly every hour in England—an appalling reality. Yet, when placed in the context of 6.7 million A&E attendances in just one quarter, the scale of violent incidents, many of which are unintentional results of delirium, becomes a different, though still serious, proportion.

The Pervasive 'I've Been Lucky' Syndrome

This disconnect between personal experience and national perception is a known phenomenon. Pollster Ipsos has tracked it for decades, finding people consistently rate their local NHS, council, or police service more highly than the national picture. This "I've been lucky" syndrome means dismal headlines often outweigh the evidence of one's own eyes, a significant challenge for politicians.

There are genuine reasons for public pessimism, from flatlining living standards to austerity's impact on services. However, NHS data is showing slow improvement: waiting lists fell in 2025 despite it being the service's busiest year. Notably, under Labour's focus, lists are falling three times faster in areas with the highest unemployment.

Yet, as Ipsos notes, politicians rarely get credit for incremental progress. The public's concern simply shifts to the next problem. The lesson from a routine broken wrist is that while the NHS faces severe and well-documented pressures, including the "torture" of corridor care, the day-to-day reality for millions of patients is often one of calm, competent, and timely care—not mere luck.