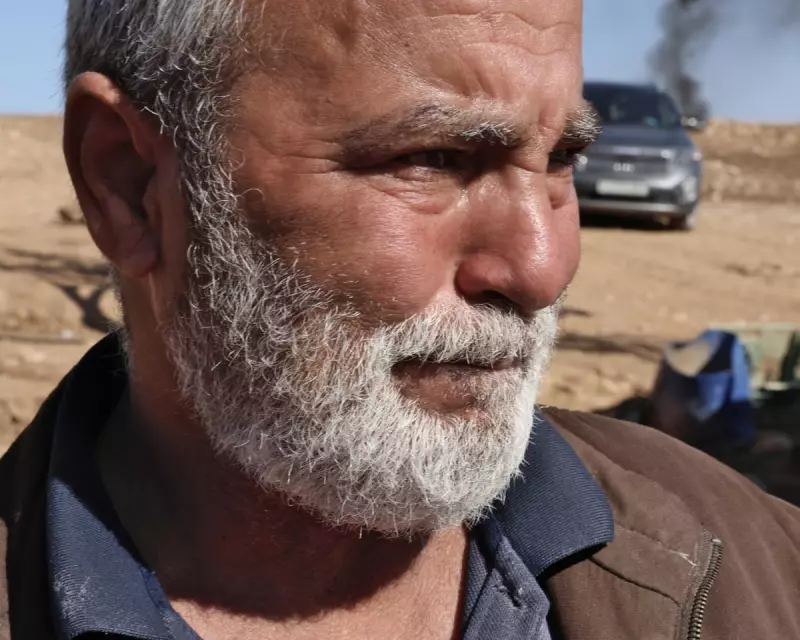

Tears streamed down the face of Mahmoud Eshaq, a 55-year-old man who had not cried since childhood, as he watched his family dismantle their home. After five decades in the south Jordan Valley, his entire life was being packed into a truck in a single, devastating day. The forced exodus from the Palestinian village of Ras ‘Ein al ‘Auja was underway.

A Community Erased, Hill by Hill

Ras ‘Ein al ‘Auja was once the largest and most established of the Bedouin villages scattered across the hillsides in this part of the occupied West Bank. Home to about 135 families, it was a community where generations had grown up gazing at the mountains across the Jordan River and playing in the dry riverbeds. By the start of this year, it stood alone.

A relentless campaign of settler violence – involving arson, mass theft, severe beatings, intimidation, and property destruction – had systematically emptied neighbouring villages. The last remaining families in nearby Mu’arrajat fled in July 2023. According to settlement monitor Kerem Navot, Israeli settlers now exert full control over more than 250 square kilometres of land in this area, a region the international community considers part of a future Palestinian state.

"We were living here peacefully, but they made us into an enemy. The settlers brought the violence," Eshaq said, his voice breaking. "I haven’t cried my whole life, but this morning I was crying. This is a terrible day for us."

The Mechanics of Displacement: Shepherds and Impunity

The project to remove Palestinians from these arid, grazing lands has accelerated since the war in Gaza began, exploiting the shift in global attention. Sarit Michaeli of B’Tselem noted that settler leadership saw an "unprecedented opportunity to step up ethnic cleansing for the area."

The method is deceptively simple and brutally efficient. Instead of slow, expensive construction, settlers use state-funded herding outposts. Teenage boys and young men, some minors in a state programme for at-risk youth, manage flocks of sheep, goats, and camels. These "Hilltop Youth" use the animals to intimidate, isolate, and ultimately bar Palestinians from their own land, a tactic celebrated in settler WhatsApp groups.

This violence operates with near-total impunity. Israeli security forces regularly arrest Palestinian residents and Israeli peace activists in the area, but consistently ignore or even support settler attacks. In one incident, after a court ordered the army to facilitate the return of Palestinians to Mu’arrajat, soldiers withdrew after only a few hours, allowing settlers to immediately drive the families out again.

The political backing is overt. Settlers have been equipped with all-terrain vehicles handed out at public ceremonies by far-right ministers like Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, himself a settler. Meanwhile, over 1,000 Palestinians have been killed by soldiers or settlers across the West Bank since October 2023, with no convictions for any of these deaths.

The Final Straw and a Desperate Choice

For Ras ‘Ein al ‘Auja, the tipping point came in the new year. Settlers ploughed up a vital dirt track, cutting off several houses, and established a makeshift outpost inside the village boundaries. They roamed at night, severing electricity cables, emptying water tanks, and pushing into rooms where women and children slept.

On a Thursday in late January, 26 families – more than 120 people – decided the risk of staying was too great. Their departure left Mahmoud Eshaq’s family on the frontline. After nights without food or sleep, and following a settler raid on his neighbour’s home, Eshaq also made the agonising decision to leave. Hiring a truck cost 1,800 shekels (£425), a small fortune, with no certain destination.

Each departure makes those who remain more vulnerable. Na’ef Ja’alin, a father of ten, stays out of sheer desperation. "The ones who have left have family who can give them a plot of land. Me and my brothers have no place to go," he said. "I have no money, and land is very expensive."

A Mainstream Israeli Project with Deep Roots

While executed by violent extremists, the goal of annexing the Jordan Valley is a long-standing, mainstream project in Israeli politics. Soon after the 1967 war, Labor minister Yigal Allon proposed a plan to retain a strip of land along the valley as a security buffer. Though never officially adopted, his vision persists.

The territory he earmarked – which includes Ras ‘Ein al ‘Auja – lies between Highway 90 and the winding mountain route Israelis call the "Allon Road." Settler leaders are explicit about their ambitions. After the destruction of another village, Mughayyir al-Deir, settler Elisha Yered posted, "This is what redemption looks like! God willing, one day we will force you [Palestinians] to the places you belong."

Across the West Bank, settlers have now seized over 18% of the land designated for a future Palestinian state. Despite sanctions from the UK, Canada, and other nations, and symbolic recognition of Palestinian statehood, the displacement continues unabated. "The culprits are so well known," says Michaeli, "but unfortunately I think we are much further from any sort of international accountability than ever."