The question of whether a film is art or exploitation is a familiar one, often centred on depictions of sexuality. But a more complex and modern debate is taking centre stage in cinema: is it grief-porn or grief-art?

The Emotional Contract of On-Screen Loss

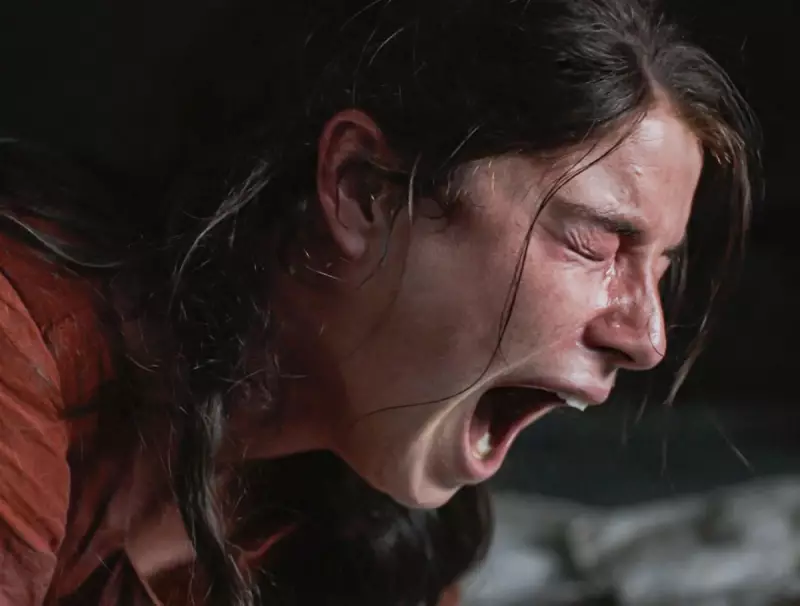

This debate is particularly relevant for a new wave of films exploring profound female grief, led by the recent adaptation of Maggie O'Farrell's novel, Hamnet. The film stars Jessie Buckley and Paul Mescal as Agnes and William Shakespeare, grappling with the death of their 11-year-old son from the plague. On paper, it has all the hallmarks of art: magnetic performances, sumptuous visuals, and intelligent, spare dialogue.

Yet, the film's power is judged almost entirely by its ability to make the audience feel. The logic becomes circular: a grief film is validated as art if it makes you feel deeply. If it leaves you cold, branding it as manipulative 'grief-porn' is an easy critique. This places the burden of proof on the viewer's emotional response.

Birds, Women, and Elemental Sorrow

A key theme linking these films is a deep, almost mystical connection between grieving women and the natural world—specifically, birds. In Hamnet, Agnes has a hawk, a symbol of her free spirit. This mirrors the narrative of H Is for Hawk, the film adaptation of Helen Macdonald's memoir, where Claire Foy retreats into isolation with a goshawk after her father's death.

These stories suggest that true, world-stopping grief is a feminine domain. Buckley's Agnes feels premonitions rooted in maternal love, while Foy's Helen uses her bond with a bird to defiantly halt time. The emotional presentation is all-consuming; you either join the character in their mire of feeling or you are an outsider. This singular focus, critics argue, can tip into the prescriptive territory of grief-porn.

The ornithological symbolism is potent but sometimes contentious. Bird enthusiasts noted that Hamnet used a Harris's hawk, a species not found in 1580s England. More broadly, birds in recent cinema—from the macaw in Julia Louis-Dreyfus's Tuesday to the crow in The Thing With Feathers—are no longer symbols of liberation but of death itself.

Humor, Gender, and the Grief Litmus Test

One telling difference between grief-art and grief-porn may be its capacity for humour. Tuesday stands out for finding genuine comedy in denial, as Louis-Dreyfus's character frantically avoids her daughter's impending death. Most films in this genre, however, treat grief with unwavering solemnity. The absurdity that often accompanies real-life loss is largely absent.

The portrayal of masculine grief also follows a different, often less valued, track. In The Thing With Feathers, starring Benedict Cumberbatch, a man's inarticulate sorrow is seen as a shortcoming rather than profound mystique. As director Chloé Zhao suggested of Hamnet, the valorised 'feminine consciousness'—drawing on intuition and community—is presented as the deeper path, even when a character's actions may not fully reflect it.

Ultimately, whether a viewer sees these films as exploitative or artistic may come down to personal resonance. The debate itself reveals much about our expectations of emotion, gender, and authenticity in cinema. As these stories show, there is no single way to grieve—on screen or off.