For years, the image of the digital nomad – working from pristine beaches and exotic jungles – has been sold as the ultimate freedom. But for one man who lived it for decades, the reality was a profound sense of emptiness and depression.

From Scottish dropout to jungle explorer

Tom Slater, now 52, began his lifelong journey at 17. After clashing with his academic father in St Andrews, Scotland, he was given a one-way ticket to Australia with just £150. "I think he was just desperate. He didn't know what to do with me," Tom recalls.

His start was harsh. Arriving during Australia's hottest winter on record, he found farming jobs barred to foreigners. Broke and inexperienced, he slept rough before finding work with a travelling funfair. "I slept in the back of a lorry and woke up with diesel oil all over my body," he remembers. Yet, even then, he felt a pull towards freedom.

After months picking cantaloupes, he funded travel to the Pacific Islands and later joined a World Wildlife Fund grant in Borneo. Living with the Iban tribe, he hunted bush animals and helped discover a plant unknown to Western science. "It was incredible; like travelling back in time," he says. For a while, he believed he could vanish into this simpler life, free from societal expectations.

The endless chase and the creeping fog

Tom became an early prototype of the modern digital nomad, funding travels through call centre work, scuba diving, and filmmaking. He lived across Egypt, Malaysia, Guatemala, Thailand, India, and countless other locations throughout his 20s and 30s.

Despite the dazzling backdrop, a persistent darkness followed. Even while scuba diving daily in paradise, he felt bored and gloomy. On a beach in Ko Pha Ngan, Thailand, with no responsibilities, he felt only emptiness. "The biggest choice I had to make that day was what I was eating for lunch, and I just felt empty and unfulfilled," he told Metro.

His mental health deteriorated severely. "There were periods where I literally didn't get out of bed for three months, apart from to eat," he admits. A visit to a GP in Scotland led to an offer of medication, but Tom sought a deeper solution.

Success without fulfilment

A breakthrough seemed to come in Varanasi, India, where he discovered a bank run by children. He successfully pitched a documentary, securing approximately £110,000 from global production companies. "I thought I'd found my thing. Everyone was saying how talented I was. But I just felt so much stress," he explains.

The tragic suicide of his Oscar-winning friend, Swedish filmmaker Malik Bendjelloul, was a pivotal moment. "It made a lot of people, including myself, think more deeply about what I was doing and why," Tom says. He eventually abandoned the project, turning down an additional £30,000, and returned to England, adrift and nearing 40.

The turning point: Stopping the escape

Tom's epiphany came through somatic therapy, which focuses on how emotions manifest in the body. He realised his decades of travel were less about exploration and more about running away. "I realised I'd felt so lost. I was trying to get away from my problems, and every time I slowed down, I felt terrible," he remembers.

This realisation aligns with broader research. A recent bunq Global Living Report found one in three digital nomads struggles with mental health, while 19% cite missing loved ones as the hardest part of the lifestyle.

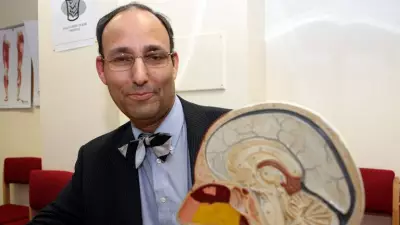

For the first time since his teens, Tom felt the "black fog" lift. He channelled his insight into a coaching business, Sapience, where for the past decade he has helped others find peace through retreats and mentoring.

The curated lie and a new purpose

Tom is now a vocal critic of the "idealised lifestyle" promoted on social media. "The digital nomad life is a social media lie," he insists, pointing to the heavily curated, filtered reality presented by influencers. He connects this pressure to broader mental health crises, including high male suicide rates.

Through his work, he sees a common thread: material success does not guarantee happiness. "I've got a number of billionaire clients who feel this way," he reveals. "They're living in a huge house that feels empty."

Now settled in South Devon and planning a move to the US with his partner, Tom reflects without regret. "I have never owned a house, had a mortgage, a car or an overdraft. But doing what I do now, I have so much purpose and community," he says.

His hard-won wisdom is simple: "It took me 20 years to realise that you can't outrun unhappiness. In the end, I just stayed still until happiness found me."