In a culture obsessed with productivity and relentless effort, a counterintuitive truth is emerging: the most effective way to tackle a stubborn problem might be to step away from it entirely. Engaging in undemanding, mundane activities can unlock the brain's latent capacity for lateral thinking, leading to breakthroughs that focused labour cannot achieve.

The Eureka Moments Born from Idle Time

History and modern science are filled with examples of great ideas born not at the desk, but in moments of distraction. The eminent cancer surgeon Professor Michael Baum experienced a pivotal moment not in the operating theatre, but during a night out. While watching Tom Stoppard's play Arcadia, a scene explaining chaos theory sparked a revolutionary connection in his mind. He wondered if the same mathematical principles could explain the erratic growth patterns of cancer.

This single thought, entertained during a theatre interval, led directly to an innovation in chemotherapy treatment and a subsequent rise in patient survival rates. As Baum later wrote, the playwright had inadvertently saved countless lives, simply by providing the mental space for a connection to form.

This phenomenon is far from unique. Agatha Christie famously plotted her intricate murder mysteries while performing the mechanical task of washing dishes. The ancient scholar Archimedes shouted "Eureka!" upon discovering the principle of buoyancy while relaxing in his bath. These stories point to a powerful cognitive process: when the conscious, busy mind is occupied with a simple task, the subconscious is freed to make unexpected and creative leaps.

The Neuroscience of "Switching Off"

This state is distinct from both concentrated work and passive loafing. It involves a gentle engagement that allows the brain's deeper processes to "percolate" information. Experts compare it to the function of dreaming, where the mind reorganises and makes sense of the day's events without conscious direction.

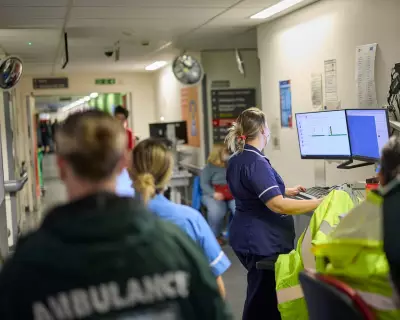

The busier and more intense our lives become, the more critical this mental downtime is. However, modern work culture is systematically eroding it. A recent TUC survey revealed that over half of British workers feel their jobs have intensified. This is particularly acute for women, who are disproportionately employed in pressured public sector roles in health and education, where shrinking resources and rising demands have eliminated all slack from the day.

The consequence is a workforce too exhausted for creative thought, both during office hours and at home. What is lost is the "free-floating" time that allows for intellectual curiosity and the kind of sideways thinking that leads to original ideas.

A Lesson for Government and the Future of Work

The principle applies not just to individuals but to institutions. A former Downing Street aide recently suggested, only half in jest, that governments should adopt a version of the university "reading week"—a dedicated period for reflection and strategic thought, away from the relentless news cycle.

This lack of reflective time may partly explain criticisms that some administrations lack a grand vision or intellectual depth. There is simply no space for ideas to mature or for lessons from past policies to be properly absorbed.

Paradoxically, the rise of artificial intelligence could offer a path to reclaiming this vital cognitive space. As AI automates routine tasks, employers face a critical choice. They can use the gained time to simply cut jobs and boost short-term profits, or they can invest in long-term creativity by granting employees time for the kind of innovative thinking and training that machines cannot replicate.

An historical template exists in Google's famed "20% time" policy of the 2000s, which allowed engineers to spend one day a week on passion projects. While many ideas failed, the policy famously bred major innovations like Gmail, on the understanding that valuable breakthroughs require the freedom to experiment.

For now, the lesson for individuals is clear. As we navigate the demands of January, granting yourself permission to potter, to daydream, or to engage in a simple task might be the most productive thing you do. The solution you've been straining to find could be waiting for you just as you stop looking.