Britain stands on the brink of losing a cornerstone of its industrial heritage and economic security, as a crisis in the chemicals sector threatens to end the nation's centuries-long self-sufficiency in salt.

The Final Nail for a Foundational Industry?

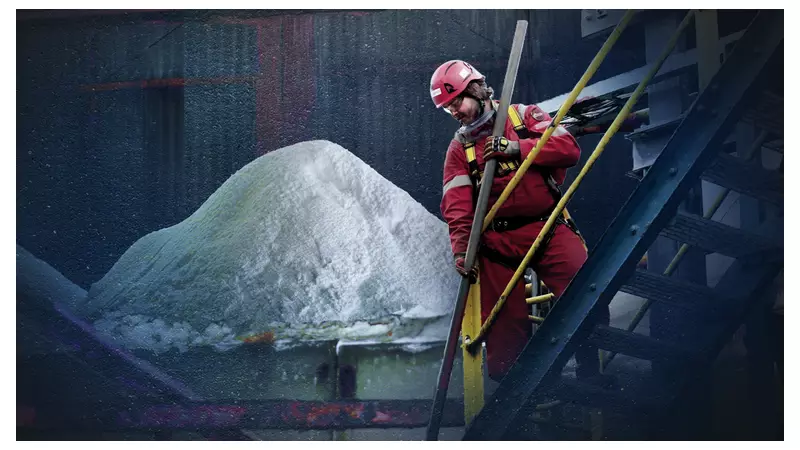

For hundreds of years, long before the Industrial Revolution, Britain has produced all the salt it required. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, it was the world's largest exporter, using this vital commodity as a tool of imperial power. Today, that legacy is under dire threat. Inovyn, which produces roughly 50% of Britain's salt, has warned it may be forced to close its Runcorn plant without government support. This would force the UK to rely on imported salt for the first time in modern history.

"Without a plant like this, we'd have to import," explains Tom Crotty, group director of chemicals at INEOS, which owns Inovyn. He highlights the dual problem: salt is corrosive and difficult to transport, and as a low-value product, shipping costs dramatically inflate its price. This would make UK food and other industries uncompetitive.

A Deeper Crisis in Core Manufacturing

The potential loss of 'salt independence' is merely the tip of the iceberg. The UK's entire chemicals sector, once a global leader and the bedrock of manufacturing supply chains, is experiencing a collapse unseen outside of world wars. Output has plummeted by 20% in just the last three years.

Sky News research reveals that over the past decade, 11 major chemical plants have shut down, many producing foundational chemicals critical for everything from fertilisers and explosives to glass and pharmaceuticals. These closures have often occurred with little public notice.

Last year, Tata Chemicals Europe ended 150 years of production by closing its soda ash plant in Lostock. Soda ash, a commodity first made in the UK during the Industrial Revolution, is essential for manufacturing glass and paper. Its production in Britain has now ceased entirely.

Similarly, Britain no longer produces its own ammonia for fertilisers, following the permanent closure of the CF Fertilisers plant in Billingham, Teesside. Inovyn has also shuttered its sulphuric acid plant in Runcorn. These shutdowns have stark implications for national security, as both ammonia and sulphuric acid are critical for producing explosives.

Energy Costs and Aged Infrastructure

The primary driver of this industrial exodus is the UK's sky-high industrial energy prices. Chemical production is intensely energy-intensive, making it far cheaper to operate in countries like the US and China. This is compounded by additional carbon taxes faced by UK firms.

Furthermore, much of the nation's chemical infrastructure is extremely aged, with some equipment dating back a century. Much of this hardware was installed by the fallen giant ICI and is now operated by smaller, fragmented companies. Their gradual demise has largely gone unnoticed.

The scale of the decline is viscerally clear at the vast Wilton Site on Teesside, once the heart of Britain's petrochemical industry. The recent shutdown of Sabic's ethylene cracker has left a hollow shell. Peter Huntsman, CEO of Huntsman International, which runs one of the last remaining plants there, described the scene as "terribly depressing."

"This is what makes things. This is where electricians and pipe fitters and welders and drivers and hauliers [work]. This is what makes your middle income," Huntsman stated. "Without it, you're just a service industry, just a service economy."

Sticking Plasters and Net Zero Tensions

The government offered a lifeline in December with a grant to support INEOS's ethylene cracker at Grangemouth, preventing its closure. However, the industry views this as a "sticking plaster" solution rather than a strategic fix for systemic issues.

Sharon Todd, head of the SCI charity, warns that without a broader change, more plants will close. "We've lost a huge amount of capability... I would say we've probably lost 90% of the core building blocks that we need, and Ethylene is almost the last hope," she said.

The crisis intersects with the UK's net zero ambitions, as many chemical processes are carbon-intensive. While plant closures aid emission reduction targets, they also strip the nation of critical industrial capacity. Todd argues the net zero strategy needs a "rethink" to simultaneously grow industry, create jobs, and rebuild communities.

The possible end of salt manufacturing in Runcorn represents a profound symbolic and practical watershed. It signals what could be the final blow for a foundational industry that was once the pride of the British economy, raising urgent questions about the UK's future as a manufacturing nation and its long-term economic security.