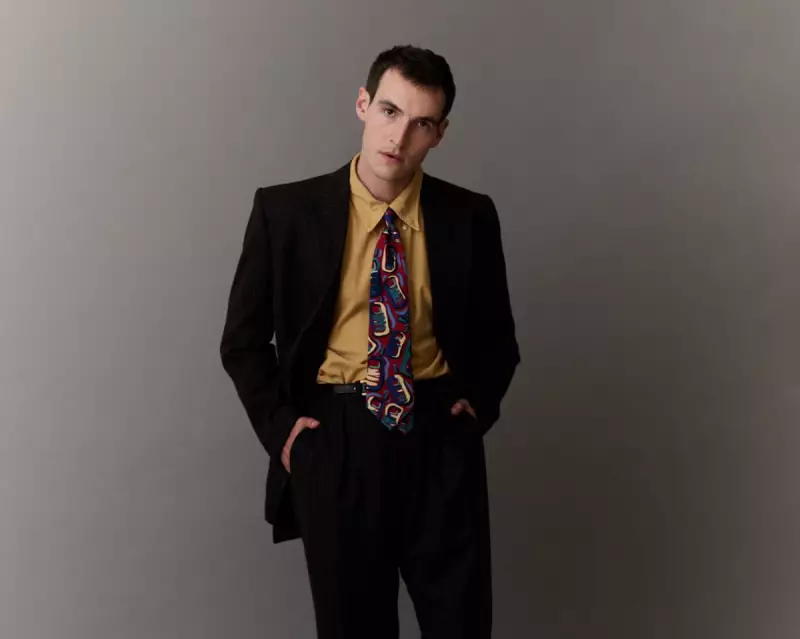

Irish actor Éanna Hardwicke is navigating two of Ireland's most contentious cultural moments simultaneously: portraying football legend Roy Keane in the new film Saipan and taking the stage in a play that once provoked riots in Dublin. In an interview at London's National Theatre, the rising star reflects on national identity, artistic empowerment, and the enduring legacy of a 23-year-old sporting feud.

Stepping into Keane's Boots for 'Saipan'

Hardwicke stars in Saipan, a film revisiting the explosive 2002 fallout between Republic of Ireland captain Roy Keane and manager Mick McCarthy (played by Steve Coogan) ahead of the FIFA World Cup. The incident, which saw Keane sent home after a furious rant, divided a nation. Hardwicke was just five years old at the time, recalling only "colours and shapes" and a memory of someone from his native Cork coaxing him to call Keane "a disgrace to his country".

The actor, who won a Royal Television Society Award in 2024 for The Sixth Commandment, admits he doesn't physically resemble Keane. His performance instead focuses on capturing the internal intensity and unwavering self-belief of the iconic midfielder. "You're always Roy," Hardwicke explains. "I think that's a brilliant quality in anyone who has it. I certainly don't. I'll blow with any wind."

The film, released in Irish cinemas on New Year's Day and in the UK on 23 January, carefully avoids taking sides. It presents Keane as compelling yet cold, and McCarthy as blustering yet decent. Hardwicke notes that screenings in Cork and Belfast reignited the public's visceral yearning for a different outcome. It remains unclear if either Keane or McCarthy has seen the film.

From Football Feud to Theatrical Uproar

Hardwicke's current role is another step into Irish controversy. He is performing at the National Theatre in Catriona McLaughlin's revival of J.M. Synge's The Playboy of the Western World, playing Christy Mahon. The 1907 masterpiece, which runs until 28 February, originally provoked riots at Dublin's Abbey Theatre, with audiences decrying its portrayal of Irish peasant life.

Hardwicke defends the play's language and spirit, arguing it captures the essential wildness, music, and storytelling of communal life in the west of Ireland. "These were places where you could tell stories as a way of lifting yourselves out of the doldrums," he says.

An Ireland 'No Longer Apologising'

Drawing a connection between the backlash against Synge and the national schism over Keane, Hardwicke identifies a historic tendency to "begrudge" those riding high. However, he senses a profound shift in contemporary Irish culture.

He points to global successes like musicians Fontaines DC and CMAT, a wave of phenomenal novelists, and his Playboy co-star Nicola Coughlan using her platform for advocacy. "There's a sense of Irish people taking stage in the world and not playing down their culture," Hardwicke states. He links this confidence to Ireland's colonial history and a modern, unified political voice, citing solidarity with Gaza as an example.

"We come from an island that's been colonised and denied its own language and culture for many centuries," he reflects. "So now there's a sense of: fuck it. We're emboldened now. We're empowered. We are no longer apologising."

From the football pitch of Saipan to the stage of the National Theatre, Éanna Hardwicke is embodying the complex stories of an Ireland that is finally, unapologetically, owning its voice on the world stage.