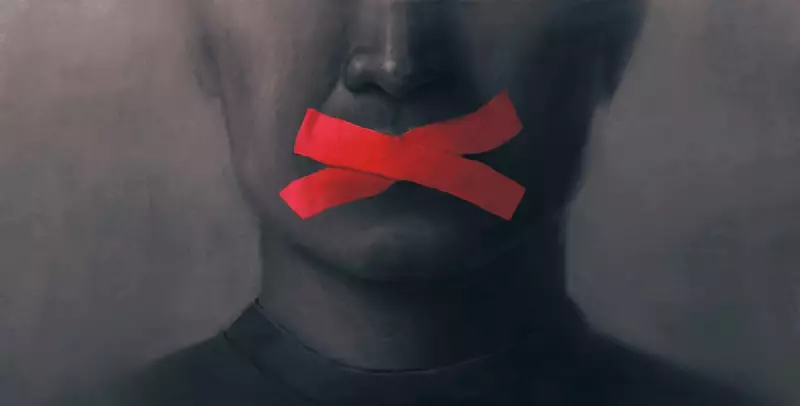

Australia's cultural landscape is facing a profound test of its principles, with the recent cancellation of the 2026 Adelaide Writers' Week highlighting a deepening crisis. Award-winning journalist Margaret Simons argues that the nation must demand its cultural leaders uphold the difficult duty of defending freedom of speech, even when they vehemently disagree with the speaker.

The Collapse of Cultural Stewardship

The controversy surrounding the Adelaide festival is not an isolated incident. Over the past year, numerous institutions have appeared to crumble under pressure before offering belated and half-hearted support for open dialogue. Simons posits that moving forward requires more than just rhetorical reflection on free speech; it demands a concrete understanding of what it entails and the burdens it places upon us.

Defending the right of individuals to express views we find deeply objectionable is exceptionally challenging. For many, it can feel like a betrayal of personal values and community allegiance. While it may be unreasonable to expect this from every citizen, Simons insists we must require it of those appointed as custodians of our culture—the directors, editors, curators, and board members of institutions like the ABC, art galleries, and writers' festivals.

Defining the Limits and Liberties of Speech

The core of the debate hinges on what freedom of speech truly means. Simons contrasts two pivotal statements from Australian legal history. In 2014, then-Attorney General George Brandis asserted in parliament that people have "the right to be bigots." Decades earlier, in 1982, Justice Lionel Murphy defended Indigenous man Percy Neal, stating he was "entitled to be an agitator" after being jailed for spitting at and abusing a white man.

Both statements concern free speech, yet they illuminate its boundaries. A right to free expression is fundamental, with widely accepted limits around incitement to violence or hatred. However, it is not a right to be respected, taken seriously, or granted a platform. A bigot may be entitled to their views, but cultural leadership involves making clear that such speech does not deserve admiration or a privileged place. Conversely, it must recognise that the speech of the oppressed is rarely polite or comfortable.

The Unenviable Task of Platforming Uncomfortable Views

This is where the role of cultural custodians becomes critical. They bear a greater responsibility than ordinary citizens to tolerate and platform challenging perspectives. Using the current example, Simons notes that Randa Abdel-Fattah is, in Murphy's terms, an agitator—which she is entitled to be. She is also an established writer and academic whose recent novel addresses pressing national issues, making her a reasonable invitee for a writers' festival, regardless of whether one agrees with her.

Similarly, while Simons was horrified by a "repugnant" column by New York Times journalist Thomas Friedman, his Pulitzer-winning record justified his 2024 festival invitation. The petition to remove him, and the counter-campaigns to cancel Abdel-Fattah, reveal a reciprocal hypocrisy among activists on all sides. For both pro-Palestinian and pro-Israel campaigners, allowing the other side a platform feels like an assault on identity and cultural safety.

The custodians' role is to rise above this. They must exercise wise judgement and hold the line, implementing free speech in practice. The failures witnessed at the ABC, in Bendigo, and in Adelaide stem from appointees who either did not understand this remit or lacked the fortitude for it.

Simons warns that governments have been careless in appointing boards, often treating positions as rewards for cronies or selecting well-meaning individuals who collapse under pressure. "Culture is not necessarily nice. Niceness is not enough," she writes. The role demands intellectual rigour, moral muscle, and courage.

The health of Australia's national conversation, its democracy, and the very character of the country depends on placing its best, most judicious, and courageous citizens in these roles. The memory of a tense but peaceful 2015 writers' festival in Myanmar, held between brutal regimes, stands as a talisman of what is possible when difficult exchanges are allowed to proceed. Australia's challenges, while significant, must be met with the same resolve.