In the marshy flatlands of Romania's Danube delta, the village of Plauru exists in a state of suspended dread. Separated from the Ukrainian port city of Izmail by just 300 metres of river, its residents are not distant observers of the war, but unwilling participants in its terrifying soundtrack.

A Daily Reality of War

For the roughly 500 inhabitants of the Ceatalchioi commune, which includes Plauru, the conflict is a daily intrusion. The deceptive daytime calm is shattered after dark by the hum of drones and the subsequent explosions that rattle windows and shake people from their beds. Since Russia intensified its attacks on Ukrainian port infrastructure along the Danube, these border communities have found themselves on a frontline of a war they are not fighting.

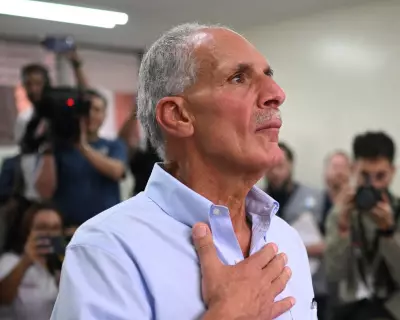

"For more than three years we have lived with war over our heads," said Tudor Cerneaga, the mayor of Ceatalchioi commune. "Some areas in Ukraine do not have the level of stress that we have here. We are on the hotline. Practically, we are part of the war too."

Isolation and the Fear of Escalation

The commune's profound isolation compounds the danger. Connected to the outside world by a single, deeply rutted dirt road to Tulcea, the nearest city, evacuation is a slow and difficult process. This risk became critically urgent in November 2023, when a Russian drone struck a Ukrainian ship carrying liquefied gas in Izmail, setting it ablaze. Romanian authorities were forced to evacuate residents from Plauru and Ceatalchioi to Tulcea.

"It was to be expected that this moment would come," Mayor Cerneaga stated. "We have been subjected to this terror for more than three years now. God forbid a drone falls on a house."

While no fatalities have occurred on Romanian soil, drone debris has repeatedly landed in fields and wetlands. The incidents have forced NATO to confront uncomfortable questions about security and escalation on its easternmost flank. In response, Romania changed its legislation in early 2025 to allow its military to shoot down unauthorised drones entering its airspace, though it has so far refrained from doing so to avoid direct escalation.

Life Under the Drones

For the villagers, a grim routine of fear and resilience has taken hold. Adriana Giuvanovici, 71, lives alone in Plauru after her husband's death. Her children live in Tulcea, but she refuses to leave. "We hear loud noises and bombs every now and again," she said. "We got used to it, but of course we are afraid."

Marius Morozov, an employee at Ceatalchioi town hall, noted a alarming increase in attacks. "When the war started in 2022 there were maybe five to seven per evening. Now sometimes it can be more than 50 in a night." He jokes with friends to cope, betting on the nightly drone count, but admits, "Sometimes you don’t sleep all night... and then you still have to come to work the next day."

The psychological toll is severe, especially on children. Ecaterina Statache said her 11-year-old daughter suffers panic attacks triggered by the blasts and cried throughout the November evacuation. For the elderly, like 70-year-old Alexandru Nedelcu, leaving is not an option. "At our age, where would we go? We are not used to the city, but we can get used to the drones and bombs."

Local resentment simmers as villagers feel neglected by the state, contrasting the support offered to Ukrainian refugees with their own plight. Mayor Cerneaga highlights the lack of clean water, proper infrastructure, and a safe evacuation route. "We help the Ukrainians but we have been abandoned," he said.

As night falls, the lights of Izmail port reflect on the Danube. In Plauru, people close their shutters and wait, knowing that a single errant drone or a decisive military response could make them the first NATO citizens drawn directly into the conflict raging just a few hundred metres away.