The political establishment, billionaire donors, and mainstream institutions threw everything they had at him. Yet, Zohran Mamdani has been elected as New York City's first socialist mayor, a victory that defies modern political narratives and taps into a deep, historic vein of the city's identity. Far from being a radical departure, Mamdani's ascent represents a return to an older, venerable Jewish tradition that helped forge modern New York: the world of Yiddish socialism.

The Direct Line to a Troublemaking Past

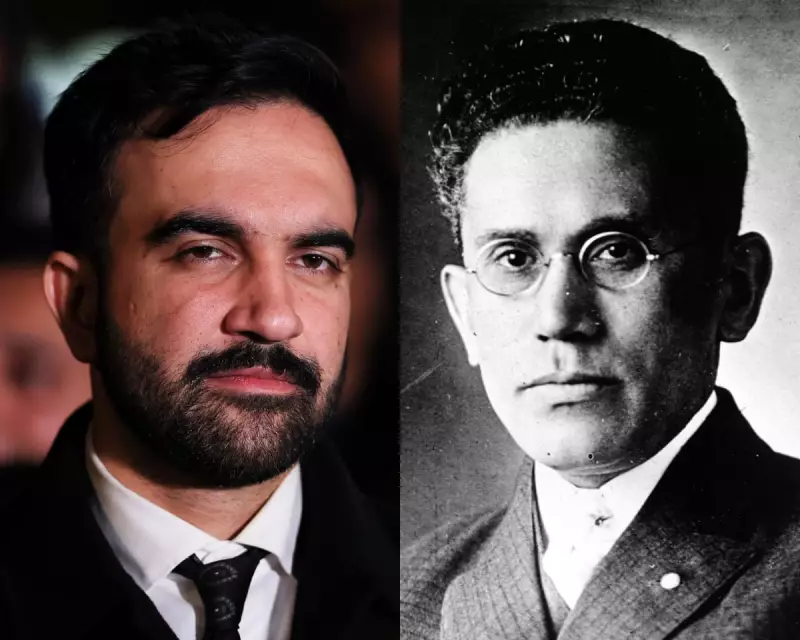

The connection is sometimes literal. A key member of Mamdani's transition team, Bruce Vladeck, carries a surname heavy with history. He is the great-grandson of Baruch Charney Vladeck, a Marxist activist from the Pale of Settlement in the Russian Empire. Arriving in New York after the failed 1905 revolution, bearing scars from a Cossack's saber, Baruch became a socialist alderman and worked in Mayor Fiorello La Guardia's administration.

His adopted name, Vladeck, was a nom de guerre from his time in the Jewish Labor Bund. This secular, socialist, and defiantly anti-Zionist movement championed the slogan "here where we live is our country"—a sentiment that resonates powerfully with Mamdani's vision for the city. In early 20th century New York, exiled revolutionaries like Vladeck found their stage.

The Fertile Ground of the Lower East Side

At the dawn of the last century, New York was home to nearly 600,000 Jews, the largest Jewish city on Earth. Crowded into Lower East Side tenements and toiling in garment sweatshops, they formed a radical, disputatious proletariat. This was the very constituency that powered Mamdani's campaign a century later.

This community built a secular, socialist, Yiddish-speaking world. Socialist Yiddish newspapers sold 120,000 copies daily. The Workmen's Circle attracted tens of thousands of members. Garment workers' unions, led by former Jewish revolutionaries, represented over 100,000 workers. In 1912, the Yiddish Forward newspaper erected a Beaux-Arts skyscraper on Rutgers Square, its facade adorned with busts of Marx and Engels—a temple to a movement seeking not just bread, but dignity and roses.

Echoes in Modern Campaigning and Backlash

Mamdani's political home, the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), mirrors this thick, cultural organising. Its blend of picket lines, educational lectures, and social events recalls the mutual aid societies and debate clubs of the past. The DSA's formidable door-knocking machine launched Mamdani's career, just as unionised garment workers canvassed for socialist candidates in the 1910s.

The parallels in backlash are equally striking. In 1918, Congressman Meyer London lost re-election after wealthy Zionists denounced his opposition to a Jewish ethnostate in Palestine. Similarly, billionaires like Bill Ackman funded vicious, albeit failed, campaigns against Mamdani, smearing him as antisemitic. Historical repression through the Palmer Raids and McCarthyism sought to erase this socialist legacy, making it easier for modern institutions to claim Mamdani's politics are foreign to New York.

A New Coalition Honouring an Old Legacy

Mamdani's campaign masterfully bridged this history with New York's present. He released ads in Spanish, Bangla, Hindi, and Arabic. He joined taxi drivers in a hunger strike for debt relief and danced with them in victory. He gave history lessons on figures like socialist birth control pioneer Fania Mindell while campaigning at queer dance parties and Diwali celebrations.

The smear tactics largely failed, particularly with younger Jews. A July poll by Zenith Research found two-thirds of Jews under 40 supported Mamdani. Beyond moral outrage over Gaza, the appeal lies in a return to a politics of material needs: affordable rent, free childcare, and reliable public transport.

Zohran Mamdani does not walk in the tradition of ritzy Upper East Side synagogues. He walks in the older, grittier tradition of so many New Yorkers' great-grandparents: the socialist sweatshop workers who fought, organised, and believed in a better and more beautiful world. His victory is not an anomaly, but a homecoming.