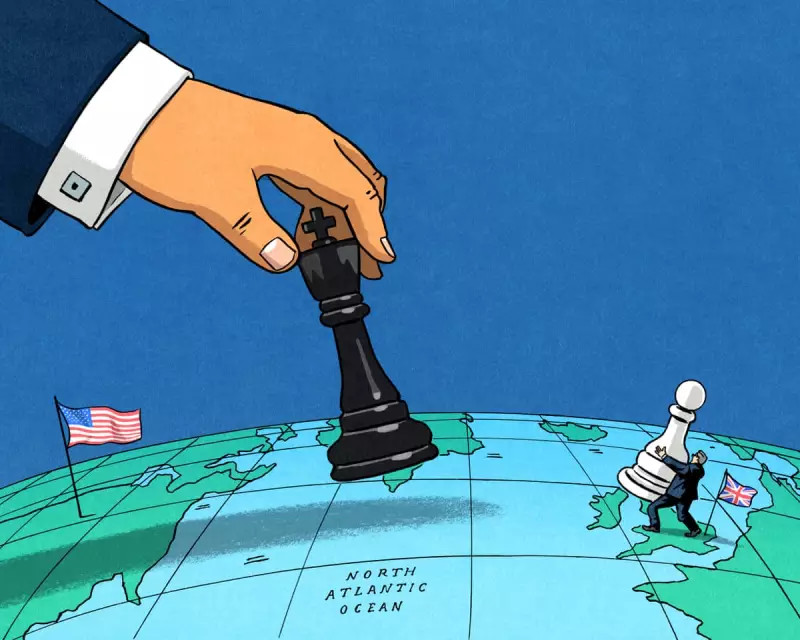

While former US President Donald Trump dominates global headlines with aggressive foreign policy moves, UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer has kicked off 2026 by publishing a colour-coded map of which councils are fixing potholes. This stark contrast in political ambition and the use of power forms the core of a damning critique of the current Labour government's timid approach.

A Government of Minor Interventions

Barely eighteen months into his tenure, with crucial elections looming and his party trailing figures like Nigel Farage and Kemi Badenoch, Starmer's flagship geographic intervention was this pothole tracker. His response to major crises has been similarly muted. When the AI service Grok, linked to the spread of child exploitation material, sparked public fury, Starmer merely threatened Elon Musk's X platform with the loss of its "right to self-regulate"—a weak stance compared to other nations which simply suspended the service.

The pattern continued during the severe water crisis in Kent and Sussex this winter. For the second time, South East Water left tens of thousands of homes, schools, and businesses without supply. The failure was so profound that even traditionally pro-market Tory MPs demanded the company's boss resign, while the Liberal Democrats called for its licence to be revoked. Starmer's response? He declared the situation "totally unacceptable," a phrase emblematic of his government's preference for rhetoric over decisive action.

The Trump Lesson in Wielding Power

This is not to praise Donald Trump, a figure described as a "know-nothing vainglorious bully." However, his approach demonstrates a profound lesson for the left: political power can matter if wielded with clarity and purpose. Despite being the most anti-government president since Ronald Reagan, Trump consistently shows how governmental levers can be pulled to achieve goals, whether through pressuring the Federal Reserve or taking unilateral military action.

Meanwhile, the centre-left in both the US and UK often retreats behind process and rulebooks. When Trump's administration illegally kidnapped a foreign leader, top Democrat Hakeem Jeffries focused his criticism on the lack of congressional authorisation and notification, not the morality of the act. Similarly, as Trump publicly hounds Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell with personal insults and investigations, centre-left commentators bemoan the damage to institutional independence rather than highlighting how such authoritarianism serves to enrich the president's circle.

The Neoliberal Trap and a Failing Status Quo

This priggish adherence to technocratic process has its roots in the neoliberal shifts under Bill Clinton, Tony Blair, and Gerhard Schröder. It has eroded the centre-left's traditional voter base, leaving its chief claim to legitimacy as expertise in managing the rulebook, not changing lives. Consequently, while Trump confronts global storms and the bond market, Starmer and Chancellor Rachel Reeves cite the bond market as the primary reason for their inaction.

When Andy Burnham recently criticised his party's subservience to financial markets, he was ridiculed by the Labour leadership. Yet his underlying point stands: a government cannot rule against its own people and expect to retain power. A chancellor cannot create rigid fiscal rules and then use them as an excuse for paralysis. The critique of unelected bodies like the Bank of England should not be ceded solely to figures like Nigel Farage.

For Starmer, radicalism was never on the agenda. His government operates through grids, anonymous briefings, and getting "both sides around the table." The stakes are kept miserably low, focused on internal party purges and career advancement. For voters in Britain for whom the system is broken, the contrast with leaders who treat politics as a tool for achieving tangible results is painfully clear. The answer to populist action is not a resigned shrug, but a compelling, decisive alternative. The current Labour administration has yet to provide one.