A new and deeply disturbing exposé has laid bare the grim reality of food within the United States' vast prison system, revealing how meals are used as a tool of punishment and control.

Eating Behind Bars, a book by ethnographer Leslie Soble, details a landscape of culinary neglect where incarcerated people are routinely served unhealthy, inedible, and sometimes dangerous food, with devastating consequences for their health and dignity.

The Daily Reality: From Mystery Meat to Maggots

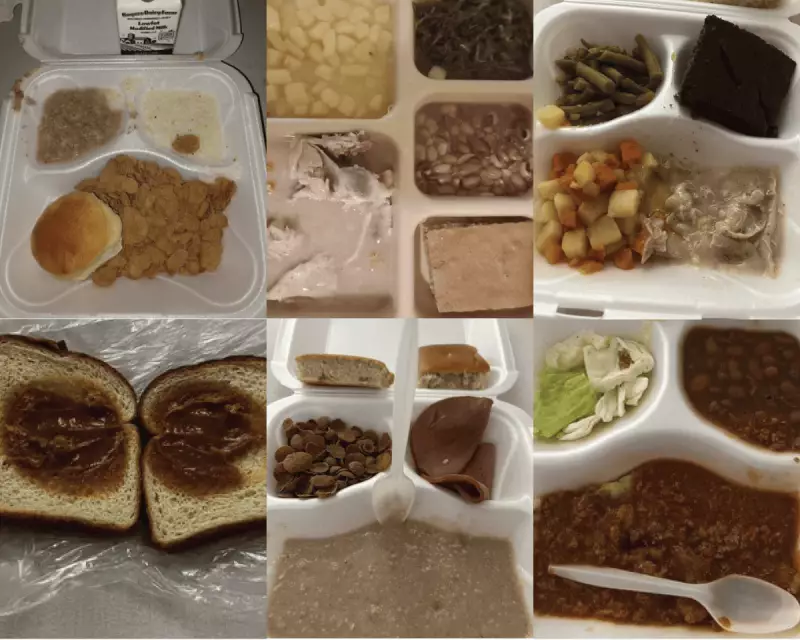

The book paints a stark picture of the average prison diet. Residents subsist on what Soble describes as "carb-heavy, ultraprocessed foods" designed merely to keep them alive, not to nourish.

Typical meals include unidentifiable "mystery meat", sour-smelling pasta, and baloney sandwiches. Fresh produce is a rarity, often replaced by wilted lettuce or, in the worst cases, maggot-infested fruit.

Testimonies collected from hundreds of formerly incarcerated people speak of finding roaches, rats, and even metal shavings in their food, alongside undercooked chicken and spoiled, curdled milk.

Food as an Additional Sentence

Soble argues that this systemic failure constitutes a form of "gastronomic cruelty" and "culinary malpractice". The consequences extend far beyond an unpleasant meal.

This poor nutrition acts as an additional, unspoken punishment, with many entering prison in one state of health and leaving with exacerbated or new conditions like diabetes and high blood pressure.

The emotional toll is severe. Being consistently served food that is harmful and unappetising erodes a person's sense of self-worth. Strict rules in dining halls can turn basic acts, like sharing an item with a friend, into infractions punishable by having trays confiscated or even being sent to solitary confinement.

A Public Health and Labour Crisis

The crisis has widespread implications. It is a significant public health issue, with estimates suggesting each year behind bars reduces life expectancy by two years.

It is also a labour rights scandal. Incarcerated people often work for pennies per hour in prison kitchens or agricultural programmes, producing food they are forbidden from eating.

In a haunting echo of the nation's past, some work on the grounds of former plantations, growing fresh vegetables and meat that is then sold for state profit, while they face punishment for taking a single tomato.

Glimmers of Hope and Systemic Barriers

Despite the bleak landscape, the book highlights reform efforts. Advocacy groups, particularly those led by formerly incarcerated people and their families, are pushing for accountability.

One promising initiative is the Harvest of the Month programme in California, run by Soble's organisation, Impact Justice, in partnership with the University of California and the state's Department of Corrections.

This scheme brings fresh, local produce like strawberries, asparagus, and lemons into facilities. The impact is profound but simple, underscoring how basic dignity is routinely denied.

However, adopting the more humane practices seen in countries like Norway and Iceland faces major obstacles in the US. The primary barriers are the nation's culture of mass incarceration and its punitive attitudes towards those behind bars.

With nearly 2 million people locked up, often for decades, the system is designed for scale and cost-cutting, not care or rehabilitation. Soble concludes that until society views incarcerated people as deserving community members, parents, and siblings, policy and funding will not fundamentally change.

Eating Behind Bars serves as a powerful indictment, arguing that the food on a prison tray sends a clear message about how a society values its citizens, even those it has chosen to punish.